Samuel_Alito_Supreme_Court_nomination

Samuel Alito Supreme Court nomination

United States Supreme Court nomination

On October 31, 2005, President George W. Bush nominated Samuel Alito for Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States to replace retiring Justice Sandra Day O'Connor. Alito's nomination was confirmed by a 58–42 vote of the United States Senate on January 31, 2006.

| Samuel Alito Supreme Court nomination | |

|---|---|

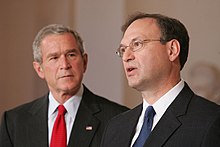

Alito, accompanied by President Bush, speaks at the announcement of the nomination | |

| Nominee | Samuel Alito |

| Nominated by | George W. Bush (President of the United States) |

| Succeeding | Sandra Day O'Connor (associate justice) |

| Date nominated | October 31, 2005 |

| Date confirmed | January 31, 2006 |

| Outcome | Approved by the U.S. Senate |

| Vote of the Senate Judiciary Committee | |

| Votes in favor | 10 |

| Votes against | 8 |

| Result | Reported favorably |

| Senate confirmation vote | |

| Votes in favor | 58 |

| Votes against | 42 |

| Result | Confirmed |

Alito was a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit at the time of his nomination to the Court. He had been appointed to that position by the president's father, President George H. W. Bush in 1990. Leonard Leo played a crucial role in successfully shepherding Alito's appointment through the Senate.[1]

On October 31, 2005, President George W. Bush nominated Samuel Alito, a federal appeals court judge with a conservative record, to succeed retiring Justice Sandra Day O'Connor on the United States Supreme Court. The announcement came four days after the president's initial choice, Harriet Miers, withdrew herself from the confirmation process.[2] Before Bush chose Miers, Alito's name was among those frequently mentioned a possible candidate for the seat.[3]

In announcing Alito's nomination, Bush stated, "He's scholarly, fair-minded and principled and these qualities will serve him well on the highest court in the land. [His record] reveals a thoughtful judge who considers the legal merits carefully and applies the law in a principled fashion. He has a deep understanding of the proper role of judges in our society. He understands judges are to interpret the laws, not to impose their preferences or priorities on the people."[4] Alito, in accepting the nomination, said, "Federal judges have the duty to interpret the Constitution and the laws faithfully and fairly, to protect the constitutional rights of all Americans, and to do these things with care and with restraint, always keeping in mind the limited role that the courts play in our constitutional system. And I pledge that if confirmed I will do everything within my power to fulfill that responsibility."[4]

This section needs expansion with: supporters of the nomination. You can help by adding to it. (June 2019) |

The American Civil Liberties Union formally opposed Alito's nomination. The ACLU has only taken this step three other times in its entire history, the last time having been with the rejected nomination of Robert Bork. In releasing their report on Alito,[5] ACLU executive director Anthony Romero justified the decision by saying that "At a time when our president has claimed unprecedented authority to spy on Americans and jail terrorism suspects indefinitely, America needs a Supreme Court justice who will uphold our precious civil liberties. Unfortunately, Judge Alito's record shows a willingness to support government actions that abridge individual freedoms."[6]

Democratic senator Barack Obama said, "Though I will reserve judgment on how I will vote on Judge Alito's nomination until after the hearings, I am concerned that President Bush has wasted an opportunity to appoint a consensus nominee in the mold of Sandra Day O'Connor and has instead made a selection to appease the far right-wing of the Republican Party."[7] Another Democratic senator, John Kerry, stated: "Every American should be deeply concerned that the far right wing which prevented Harriet Miers from even receiving a Senate hearing is celebrating Judge Alito's nomination and urging the Senate to rubber-stamp the swing vote on our rights and liberties. Has the right wing now forced a weakened President to nominate a divisive justice in the mold of Antonin Scalia?"[8]

Senator Lincoln Chafee stated on January 30, 2006, "I am a pro-choice, pro-environment, pro-Bill of Rights Republican, and I will be voting against this nomination."[9]

NARAL Pro-Choice America announced its opposition to Alito's nomination by saying "In choosing Alito, President Bush gave in to the demands of his far-right base and is attempting to replace the moderate O'Connor with someone who would move the court in a direction that threatens fundamental freedoms, including a woman's right to choose as guaranteed by Roe v. Wade."[10]

The National Association of Women Lawyers "determined that Judge Alito is not qualified to serve on the Court from the perspective of laws and decisions regarding women's rights or that have a special impact on women."[11]

On November 3, 2005, Senator Arlen Specter (R), chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee outlined the prospective time line for the Alito hearing and voting, scheduling the committee's opening statements for January 9, 2006, with the hearings expected to last five days. A committee vote was to be held on January 17, and the vote of the full Senate on the nomination was to be held January 20, which would have been nearly a month later than desired by President Bush, who had pushed for a confirmation vote to be held by Christmas.

On January 9, Judiciary Committee members presented opening statements, and questioning by members began on January 10; questioning continued until January 12, after which witness statements continued until January 13. On January 16, Senator Specter's office announced that the committee vote would take place one week later than originally planned, on January 24, with the full Senate to take up debate on the nomination the following day.

Day 2 (Jan. 10)

Committee Chairman Specter addressed the unitary executive theory. He asked Alito about his understanding of the Truman Steel Seizure case, Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, and about the Court's theory of "super precedent," recently articulated by Chief Justice John Roberts. In a humorous motion Specter said super-duper precedent as regards the Casey case.

Alito was questioned about his membership in the Concerned Alumni of Princeton (CAP), described in some media reports as a racist, sexist organization that sought to restrict the admission of women and minorities to the private institution. When questioned by Senator Patrick Leahy (D) about his involvement, Alito claimed to have no memory of being a member of the group. However, in his 1985 'Personal Qualifications Statement' when applying to be an Assistant Attorney General, he listed his membership in CAP as a qualification. Leahy stated "I can't believe at age 35 when applying for a job" that he couldn't know. It was subsequently pointed out by several senators that several alumni of Princeton, Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist (R) and former Senator Bill Bradley (D) had publicly deplored the group's activity. Senator Orrin Hatch (R) pointed out that Alito was not an officer of CAP, and also asked Alito "Are you against the admission of women or minorities?" Alito replied "Absolutely not, Senator. No".[12]

Alito did not immediately recuse himself from a case involving the low-cost mutual-fund company Vanguard. Senator Hatch addressed this issue, citing the American Bar Association's Standing Committee on Federal Judiciary as saying (after investigating the Vanguard nonrecusal), "Judge Alito ... is of the highest ethical standing." Alito then was allowed to explain the facts of the Vanguard case. Alito asserted that he abided by Section 455 of Title 28. Senator Ted Kennedy (D) reminded Alito that he had testified that he would recuse himself during his 3rd Circuit Court confirmation. Alito said that it was a pro se case (meaning it was not argued by a lawyer). He stated that the court handles pro se cases differently from cases argued by lawyers. He said that the recusal forms are different. The Vanguard case, he said, did not come to him with "clearance sheets," just the sides briefs. "When this case came to me, I didn't focus on recusal," he said. On appeal, a recusal motion came to him and he then stated that he had "gone to the Code" and did not feel he needed to recuse. He stated that he decided to recuse himself and requested that his decision on the case be vacated. He said that his procedure for pro se cases now uses red sheets for recusals, to avoid missing them.

Seeking to allay liberals' fears of creeping federalism that could hamstring Congress as in United States v. Lopez, Senator Jeff Sessions (R) asked Alito about the required interstate nexus before a federal statute can be applied. Alito explained that in his experience as United States Attorney, federal gun crime statutes can satisfy the required jurisdictional element by saying that the gun must have been transported in interstate commerce. Senator Sessions tried to do damage control over the controversial Garrett v. Alabama case that the conservative 5-4 majority used to grant more states' rights via their federalism jurisprudence holding that Congress may not grant a state citizen the right to sue his or her own state for money damages. Senator Sessions asked about Alito's views on the reading of foreign legal precedents, allowing Alito to express his support for Antonin Scalia's well-known opposition to the consideration of foreign law in crafting opinions by U.S. judges. Alito said "I don't think that foreign law is helpful in interpreting the Constitution... There are other legal issues that come up in which I think it's legitimate to look to foreign law."

Sessions then allowed Alito to give his opinion on the case involving the strip search of a ten-year-old girl (Doe v. Groody) that opponents had highlighted as showing what they viewed as Alito's extreme deference to authority (in this case the right of the police to interpret a search warrant for a suspected drug dealer's premises as authorizing them to strip-search the man's wife and daughter).

Senator Sessions also highlighted Alito's ruling in favor of abortion rights in at least one case.

Senator Lindsey Graham (R) asked Alito questions about enemy combatants, and the Hamdi v. Rumsfeld and Rumsfeld v. Padilla cases. Graham asked whether there have ever been any cases in which a foreign non-citizen soldier/fighter brought suit in a U.S. court. Alito was asked whether any enemy prisoner of war ever brought a federal habeas corpus case. There were two cases, the Six Saboteurs, Ex parte Quirin where even U.S. citizens are not entitled to federal courts but allowed only military tribunals. Then the second case involving six Germans caught assisting Japanese (Johnson v. Eisentrager) who were sent to Germany; they brought an unsuccessful habeas corpus case. They were held "not [in] U.S. territory". Graham said, "We don't let people trying to kill us sue us." Alito said that "[he] wouldn't put it" so strongly. Alito said that we also need to take note of Ex Parte Milligan from the Civil War. Senator Graham disagreed. Alito agreed with Senator Graham that the military has expertise on who is and who is not a prisoner of war. However, the treatment of detainees, according to Graham, is a different matter. Senator Graham asked whether Alito is proud of the fact that the USA is a signatory to the Geneva Convention. Graham asked whether if someone were caught whether here or abroad a la Hamdan the Geneva Convention would give the prisoner a private right of action. Senator Graham pointed out that where he differed from some others is on the question of torture. Graham asked whether any President can disregard the federal statute against torture—making it a crime—even in war.[citation needed] Alito said "No person in this country is above the law. And that includes the President and it includes the Supreme Court."[13]

On the question of what a Strict constructionist is, Alito again agreed with Senator Graham, stating it was a judge who did not make it up. Senator Graham asked whether a President who interprets the Congressional authorization for the Use of Force as giving him the right to wire-tap without getting a FISA warrant is ... Senator Graham said that his point a la Justice Jackson (in the Youngstown Sheet & Tube v. Sawyer case) was not aimed at Alito but "at the audience". Senator Graham is worried about the "chilling effect" of a President who goes too far, leaving Congress gun-shy about granting the executive branch the "Use of Force" (i.e. declining to pass a War Resolution). Graham hinted at the 60-vote requirement for breaking a so-called filibuster (actually invoking cloture). Alito did not take the bait over whether any statute or rule could be made to overrule the simple majority that the Constitution requires for confirming a Supreme Court Justice.

Senator Charles Schumer (D) asked Alito whether statements in his 1985 'Personal Qualifications Statement' when applying to be an Assistant Attorney General under Pres. Ronald Reagan represented his views at the time and also whether they represent his views today. Alito gave an answer about stare decisis and the process he would use to consider how he would decide issues that might come before him. Senator Schumer responded, stating that Alito had stated forthrightly that "the Constitution does not protect a right to an abortion". Schumer said that "it's important that you (Alito) give an answer." Alito replied that if a case involving abortion rights came up, he would use a judicial process. Schumer rejoined ... "I'm not asking about a process;.... Do you still believe it?" Schumer remarked "I'm not asking you about case law". Schumer then asked whether the "Constitution protects the right of free speech" whereupon Alito agreed. Schumer then compared that question with the question of whether the Constitution protects the right to an abortion. Senator Schumer then made an elliptical comment about hypothetical in-laws. Schumer said that he didn't expect Alito to answer the abortion question. Schumer mentioned the National League of Cities v. Usery case and how it was overruled by Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority and how Lawrence v. Texas overruled Bowers v. Hardwick and Brown v. Board of Education overruled Plessy v. Ferguson. So Alito agreed that stare decisis is not inviolate. Senator Schumer made allusions to Justice Clarence Thomas's views on stare decisis, which he claimed included a call for Buckley v. Valeo, Calder v. Bull and a long string of cases establishing Supreme Court precedent to be overturned.

Senator John Cornyn (R) characterized Senator Schumer's questioning as of the "When did you stop beating your wife?" style and remarked that if Schumer can mention in-laws, he can mention a wife. Cornyn said that the word "abortion" is not in the Constitution; Alito said, "The word that appears in the Constitution is liberty." He further claimed that "There is no express reference to privacy in the Constitution. But it is protected by the Fourth Amendment, plus in certain circumstances by the First Amendment, and in certain circumstances by the Fifth and the Fourteenth amendments."

Day 3 (Jan. 11)

Senator Dick Durbin (D) pressed Alito to either agree or disagree with a statement by Chief Justice John Roberts that the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision was "settled law." Alito would not agree, stating that it was a matter that could come before the court, and that "it is an issue that is involved in litigation now at all levels." He did say, "When a decision is challenged and reaffirmed, it increases its value. The more times it happens, the more respect it has." Durbin suggested there seemed to be inconsistency between Alito's unequivocal support for the unspecified right to desegregated schools in Brown v. Board of Education from the equal protection clause and his refusal to do the same for the Griswold case from the liberty clause. Durbin also questioned Alito further regarding his membership in Concerned Alumni for Princeton, and Alito again denied remembering any details about his membership in the organization.

Senator Sam Brownback (R) countered with a recommendation from a former law clerk who was a member of the ACLU. On checks and balances, Brownback then asked Alito about the power of Congress to limit the federal courts' jurisdiction in the Exceptions Clause as in Ex Parte McCardle.

Senator Herb Kohl (D-WI) cited a Washington Post analysis of 221 cases where there was a 2-1 judicial split in decisions on Civil Rights cases, which found that Alito sided against 3 out of every 4 plaintiffs who claimed discrimination, a much higher rate than that of similar judges. Alito said that the sample was skewed because most of the cases were from District Court where the plaintiff lost.

Judiciary Committee Chairman Specter and Senator Kennedy had a heated exchange after Kennedy called for the committee to subpoena records of the Concerned Alumni of Princeton, in order to learn more about Alito's past involvement with the controversial group.[citation needed] There was some argument between the two senators over whether Kennedy had previously made this request to Specter via mail. This issue was later resolved during a recess when Specter was reminded that he had dismissed it as "unmeritorious." William A. Rusher, one of CAP's founders and former publisher of National Review, released the CAP records later this day.

Senator Leahy told Alito that he was "concerned that you may be retreating from part of your record." Leahy continued, "A number of us have been troubled by what we see as inconsistencies in some of the answers."

Senator Mike DeWine (R) then mentioned his concern on the Americans with Disabilities Act that the Olmsted case in 1999, in which the Supreme Court held that the state must offer disabled people access to all public facilities and programs. DeWine asked Alito if he would reconsider his decision in the earlier Helen L case in the motion for rehearing.

DeWine also asked about antitrust, where many hospitals buy using GPOs (group purchasing organizations) to get discounts. This results in smaller companies having a hard time getting into the business. He asked about the famous bundling case 3M v. LePage, in which Alito dissented (the majority found against 3M). DeWine then asked about the fact that many clauses are written in the general terms of Unlawful Search and Seizure, Cruel and Unusual ... how would Alito as a Justice know whether he was following the Constitution or whether he was making policy. Alito mentioned stare decisis and used the Terry stop search and "administrative search" and the "border search" as examples of how to follow what was done before.

DeWine then mentioned the fact pattern of the Gilleo case where homeowners were restricted on the size and type of lawn signs that they could display. He asked Alito what factors he would use to decide how to restrict speech in the public square. Alito said that the Forum Doctrine has been developed to address speech in public. DeWine asked about "commercial speech" in Pitt News where Alito struck down a local speech restricting rule. Alito said that "sufficient tailoring" was used as the standard for invalidating the ordinance that applied only to the Pitt News and not to other papers.

Day 4 (Jan. 12)

The scheduled final day of committee questioning began at 9:30 a.m. EST.

Senator Specter began by recounting the review of records relating to Concerned Alumni of Princeton by committee staff along with staff members of Kennedy. He noted that no mention of Judge Alito was found in any of the documents. The documents included contributor lists and subscriber lists for the organization's magazine, Prospect. The Senator also noted that the organization's founder stated, "I have no recollection of Samuel Alito at all. He certainly was not very heavily involved in CAP, if at all." Specter then yielded to Leahy for an opening statement before starting Leahy's allotted time.

Senator Leahy questioned Alito on subjects ranging from the death penalty to the right to die, later telling reporters "I continue to be worried -- and I pressed the questions again today, as I have all week long,...He is not clear that he would serve to protect America's fundamental rights."

Senator Kennedy began his questioning of Alito by asking him about his comment that "The concept of a unitary executive does not have to do with the scope of executive power," asserting that this comment was contradictory to others made by Alito. Kennedy again questioned Alito on his recusal list as a member of the Third Circuit Court of Appeals with regard to the Vanguard case. There is some dispute as to when the Vanguard companies were added to Alito's recusal list. Kennedy went on to say "[Alito] has failed to give us any plausible explanation."

Senator Joe Biden (D) initiated his allotted 20 minutes of questioning by asking Alito if the president has the authority to "invade Iran tomorrow without getting permission from the people, from the United States Congress, absent him being able to show there's an immediate threat to our national security?" Alito responded to Senator Biden's questioning with "... what I can tell you is that I have not studied these authorities and it is not my practice to just express an opinion on a constitutional question including particularly one that is as momentous as this."

Senator Herb Kohl (D) asked Alito, "Do you think that the courts need to consider public opinion when deciding cases?"—to which Alito responded, "I think that the courts were structured the way they are so that they would not decide their cases based on public opinion." Kohl went on to ask, "Should judges be term-limited? Should judges, at least, be age-limited?" Alito responded, "I didn't think we should look to foreign law in interpreting our Constitution, [but] I don't see a problem in looking to the practices of foreign countries in the way they organize their constitutional courts." When asked how he differs from Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, Alito said, "I would try to emulate her dedication and her integrity and her dedication to the case-by-case process of adjudication, which is what I think the Supreme Court and the other federal courts should carry out. I think that is a central feature of best traditions of our judicial system."

Senator Dianne Feinstein (D) questioned Alito on the separation of powers and the Constitutional limits on executive authority. Then, after a final round of questions and answers, Alito's public examination ended and the committee went into closed executive session.

Witness testimony

Witness testimony began with the American Bar Association's Standing Committee on Federal Judiciary after the scheduled lunch recess at 2:30.

Day 5 (Jan. 13)

Witness testimony continued.

Conflict of interest question

On a questionnaire for the Senate Judiciary Committee in his Third Circuit Court-of-Appeals confirmation process in 1990, Alito said he would avoid a conflict of interest by not voting on cases involving First Federal Savings & Loan of Rochester, NY, and two investment companies, Smith Barney and Vanguard Group, because he held accounts with them. However, in 2002, Alito upheld a lower court's dismissal of a lawsuit filed against multiple company defendants, including Vanguard Group. When notified of the situation, Alito denied doing anything improper but recused himself from further involvement in the case. The case was reheard with the new panel coming to the same conclusion.

On November 10, Alito wrote a letter to Judiciary Committee chairman Specter in which he explained his participation in the case.[14] He said that when he had originally listed Vanguard and Smith Barney in 1990, "my intention was to state that I would never knowingly hear a case where a conflict of interest existed. [...] As my service continued, I realized that I had been unduly restrictive."

During witness testimony of Alito's confirmation hearings, witness John Payton (member of the American Bar Association's Standing Committee on Federal Judiciary) testified: "In the end, he did acknowledge that it was his responsibility that a mistake and error had been made. Those cases should have been caught and he should have not heard those cases."

American Bar Association rating

Alito was rated by the American Bar Association as "Well Qualified", which is the ABA's highest recommendation. In a letter[15] to the Judiciary Committee, Chair of the ABA Standing Committee on Federal Judiciary, Stephen Tober, reviewed Alito's failure to recuse himself in Vanguard and Smith Barney matters, and a third case where a conflict was alleged. Tober concluded:

- We accept [Alito's] explanation and do not believe these matters reflect adversely on him... On the basis of our interviews with Judge Alito and with well over 300 judges, lawyers, and members of the legal community nationwide, all of whom know Judge Alito professionally, the Standing Committee concluded that Judge Alito is an individual of excellent integrity.

Committee

On January 24, 2006, the Senate Judiciary Committee endorsed the Alito nomination, sending it to the full Senate for final action in a 10–8 party-line vote. Not since 1916, concerning the Supreme Court nomination of Louis Brandeis, had the committee's vote to approve a nominee split precisely along party lines. The vote underscored the contrasting views on Alito's conservative judicial record.[16]

Filibuster threat

Some Democratic senators who opposed the Alito nomination considered using a filibuster option in the attempt to block the nomination. Barbara Boxer said, "The filibuster's on the table." While other senators warned not to rush to a decision, Dick Durbin said "I don't think we should assume that's going to happen at all." He added, "Ordinarily it takes six to eight weeks to evaluate a Supreme Court nominee. We shouldn't rush to judgment."

At the conclusion of the confirmation hearings, on January 12, the threat of a filibuster appeared to grow more remote as Durbin called a filibuster attempt "unlikely," and fellow Democrat Dianne Feinstein said, "I do not see a likelihood of a filibuster. This might be a man I disagree with, but it doesn't mean he shouldn't be on the court." She changed her position on January 27, saying that she would vote no for cloture.[17] One day earlier Senator John Kerry had publicly called for a filibuster to block Alito's confirmation, accusing President Bush of trying to make the Supreme Court more ideologically conservative.[18] Kerry called for the filibuster while at a resort in Davos, Switzerland, leading Republicans to ridicule him.[19] Despite receiving support from fellow Democrats, including Ted Kennedy and Hillary Clinton, others, concerned about the political cost of such a move, such as Ben Nelson and Mary Landrieu, opposed it.[20][21]

Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid supported the call for a filibuster, though he acknowledged it was unlikely to succeed, saying, "Everyone knows there are not enough votes to support a filibuster."[18] The effort to garner support for a filibuster indeed fizzled out, as the Senate voted to invoke cloture on the nomination 72–25, easily exceeding the 60 votes needed to pass the motion to end debate; only 24 of the Senate's 44 Democrats went along with the filibuster (the chamber's lone independent, Sen. Jim Jeffords, did as well). All of the members of the Gang of 14 voted for cloture with the majority.[22]

While expressing concern about the use of the filibuster, believing that it was both ineffective and the wrong way of going about the nomination, then senator, Barack Obama ultimately joined the attempt to filibuster Alito, due to believing that Alito's views were "contrary to core American values" [23] Obama later expressed regret over supporting the filibuster, believing that it contributed to the "broken" nomination process for the Supreme Court. [24]

Full Senate

The Senate voted 58–42 on January 31, 2006, to confirm Alito as the 110th justice of the Supreme Court. All but one of the Senate's 55 Republicans voted to confirm Alito; they were joined by four Democrats who broke party ranks and voted in his favor. This was the closest confirmation vote for a Supreme Court nominee since Associate Justice Clarence Thomas was confirmed 52–48 in 1991.[22]

- Toobin, Jeffrey (April 10, 2017). "The Conservative Pipeline to the Supreme Court". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- Gless, Andrew (October 31, 2017). "Bush nominates Alito as Supreme Court justice, Oct. 31, 2005". Politico. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- "Miers withdraws Supreme Court nomination: Bush accepts decision 'reluctantly,' promises quick replacement". MSNBC. October 27, 2005. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- "Text of Bush, Alito remarks at nomination announcement". USA Today. Associated Press. October 31, 2005. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- "American Civil Liberties Union". Archived from the original on January 12, 2006. Retrieved January 12, 2006.

- "Obama Statement on President Bush's Nomination of Judge Samuel Alito to the Supreme Court". Archived from the original on November 2, 2005.

- "John Kerry statement on nomination of Samuel Alito". Archived from the original on November 28, 2005.

- "Chafee says he will vote against Alito - Boston.com". Archived from the original on February 8, 2006. Retrieved January 30, 2006.

- NARAL Press Release Archived November 1, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- "National Association of Women Lawyers ('NAWL') Issues Evaluation of Judge Samuel A. Alito for the Position of Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court" (Press release). Chicago: The National Association of Women Lawyers. PRNewswire. January 8, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- "Transcript: U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee Hearing on Judge Samuel Alito's Nomination to the Supreme Court". The Washington Post. January 10, 2006.

- "S260 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE" (PDF). www.congress.gov.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). National Review. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 17, 2006. Retrieved November 17, 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 13, 2006. Retrieved January 31, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Reynolds, Maura (January 25, 2006). "Senate Panel Backs Alito on Party-Line Vote". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- "Senator Feinstein to Vote No on Cloture for the Nomination of Judge Samuel Alito to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court". Archived from the original on January 30, 2006. Retrieved January 30, 2006.

- Reynolds, Maura (January 28, 2006). "Filibuster option on Alito divides Senate Democrats". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- "GOP sets up showdown over Alito". CNN. January 27, 2006. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- Sisk, Richard (September 8, 2011). "Hil's for Filibuster". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on February 7, 2006.

- "Alito sworn in as nation's 110th Supreme Court justice: Senate confirms nominee 58-42 after filibuster fails". CNN. February 1, 2006. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- "U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 109th Congress – 2nd Session". Senate Vote #2 in 2006. United States Senate. January 31, 2006. Archived from the original on August 29, 2008. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- "On the Nomination PN1059: Samuel A. Alito, Jr., of New Jersey, to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States". govtrack.us. Senate Vote #2 in 2006 (109th Congress). January 31, 2006. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- Bazelon, Emily (October 31, 2005). "Alito v. O'Connor". Slate.

- "Bush choice sets up court battle". BBC..

- Dickerson, John (October 31, 2005). "Ready To Rumble". Slate.

- Espo, David (October 31, 2005). "Bush Nominates Alito for Supreme Court". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 4, 2005.

- Response to a Senate Judiciary Committee questionnaire

- Transcript of nomination

- Text of Bush's nomination of Alito

- Confirmation Hearing on the Nomination of Samuel A. Alito, Jr., to be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States: Hearing before the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, One Hundred Ninth Congress, Second Session, January 9-13, 2006

- Searchable version of confirmation hearing transcripts

- Scholarly paper, "Presidential Strategies in Supreme Court Justice Selection"