Languages_of_Nigeria

Languages of Nigeria

Languages of the country and its peoples

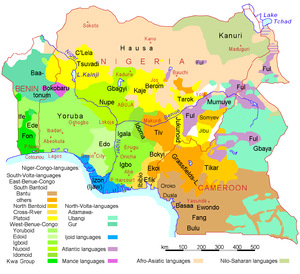

There are over 525 native languages spoken in Nigeria.[1][2][3] The official language and most widely spoken lingua franca is English,[4][5] which was the language of Colonial Nigeria. Nigerian Pidgin – an English-based creole – is spoken by over 60 million people.[5][6]

| Languages of Nigeria | |

|---|---|

A map of languages in Nigeria and neighbouring countries | |

| Official | English |

| National | Hausa, Igbo, Yoruba |

| Regional | Efik-Ibibio, Isoko, Edo, Tiv, Fulani, Idoma, Ijaw, Kamwe, Kanuri, Ukwuani, Urhobo, Nupe, Gbagyi |

| Vernacular | Nigerian Pidgin |

| Foreign | Arabic, French |

| Signed | |

| Keyboard layout | |

The major native languages, in terms of population, are Hausa (over 80 million when including second-language, or L2, speakers), Yoruba (over 54 million, including L2 speakers), Igbo (over 42 million, including L2 speakers), Efik-Ibibio cluster (over 15 million), Fulfulde (13 million), Kanuri (5 million), Tiv (5 million), Nupe (3 million) and approximately 2 to 3 million each of Karai-Karai Kupa, Kakanda, Edo, Igala, Idoma and Izon.[7] Nigeria's linguistic diversity is a microcosm of much of Africa as a whole, and the country contains languages from the three major African language families: Afroasiatic, Nilo-Saharan and Niger–Congo. Nigeria also has several as-yet unclassified languages, such as Centúúm, which may represent a relic of an even greater diversity prior to the spread of the current language families.[8]

English is the single most widely spoken language in Nigeria, spoken by 60 million of the population.[9] It is the main lingua franca of the country and there are a growing number of sole English speakers due to rapid urbanisation and globalisation.[10] English remains the official language and is the major language of communication in government, business and education.[10] Furthermore, the national anthem, constitution and pledge are written in English. Almost all mass media transmit information in English.[11] English became the official language when Nigeria was created from diverse national groups by the British Empire.[11] Despite decolonisation, Nigeria chose to make English the official language to promote national cultural unity[12] and so not to favour any particular native language.[11]

Despite its status, English is not widely spoken in rural areas.[13] Many Nigerians struggle with English, evidenced by the 60 percent fail rate of the WASSCE in English (May/June 2015), an important exam certificate.[10] Nevertheless, many Nigerians hold negative social attitudes towards the country's native languages, combining to lead to the neglect of Nigeria's many native languages. As such, there are fears from prominent linguists that Nigerian native languages are endangered and face eventual extinction.[11]

Many Nigerians speak Nigerian Pidgin, a creole language based on English, which has replaced the native language for many Nigerians. Pidgin is a popular social and cultural language.[11] It has become popular in the mass media and in political slogans.[14][15][11] According to a 2012 study, the replacement of native local languages with Pidgin is inevitable in the areas studied.[16]

The Afroasiatic languages of Nigeria are divided into Chadic, Semitic and Berber.[17] Among these categories, Chadic languages predominate, with more than 700 languages. Semitic is represented by various dialects of Arabic spoken in the Northeast and Berber by the Tuareg-speaking communities in the extreme Northwest.

The Hausa language is the best known Chadic language in Nigeria; though there is a paucity of statistics on native speakers in Nigeria, the language is spoken by 24 million people in West Africa and is the second language of 15 million more. Hausa has therefore emerged as lingua franca throughout much of West Africa, and the Sahel in particular. The language is spoken primarily amongst Northern Nigerians and is often associated with Islamic culture in Nigeria and West Africa on the whole.

Hausa is classified as a West Chadic language of the Chadic grouping, a major subfamily of Afroasiatic. Culturally, the Hausa people became closely integrated with the Fulani following the establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate by the Fulani Uthman dan Fodio in the 19th century.[18][19][20][21] Hausa is the official language of several states in Northern Nigeria and the most important dialect is generally regarded as that spoken in Kano, an Eastern Hausa dialect, which is the standard variety used for official purposes.

Eastern dialects also include some dialects spoken in Zaria and Bauchi; Western Hausa dialects include Sakkwatanchi spoken in Sokoto, Katsinanchi in Katsina Arewanchi in both Gobir and Adar, Kebbi and Zamfara. Katsina is transitional between Eastern and Western dialects. Northern Hausa dialects include Arewa and Arawa, whilst Zaria is a prominent Southern version; Barikanchi is a pidgin formerly used in the military.

Hausa is a very atypical Chadic language, with a reduced tonal system and a phonology influenced by Arabic. Other well-known Chadic languages include Mupun, Ngas, Goemai, Mwaghavul, Bole, Ngizim, Bade and Bachama. In the East of Nigeria and on into Cameroon are the Central Chadic languages such as Bura, Kamwe and Margi. These are highly diverse and remain very poorly described. Many Chadic languages are severely threatened; recent searches by Bernard Caron for Southern Bauchi languages show that even some of those recorded in the 1970s have disappeared. However unknown Chadic languages are still being reported, such as the recent description of Dyarim.

Hausa, as well as other Afroasiatic languages such as, Margi, Karai-Karai and Bade (another West Chadic language spoken in northeastern Nigeria), have historically been written in a modified Arabic script known as ajami. However, the modern official orthography is now a romanization known as boko introduced by the British regime in the 1930s.

Niger–Congo predominates in the Central, East and Southern areas of Nigeria; the main branches represented in Nigeria are Mande, Atlantic, Gur, Kwa, Benue–Congo and Adamawa–Ubangi.[22] Mande is represented by the Busa cluster and Kyenga in the northwest. Fulfulde is the single Atlantic language, of Senegambian origin but now spoken by cattle pastoralists across the Sahel and largely in the northeastern states of Nigeria, especially Adamawa.

The Ijoid languages are spoken across the Niger Delta region and include Ịjọ (Ijaw), Kalabari, Engenni and the intriguing remnant language Defaka. The Engenni language is spoken in the Ahoada-west region of Rivers State and Zarama community in Bayelsa State. The Ibibio language is spoken across the coastal southeastern part of Nigeria and includes the dialects Oron, Annang, and Efik proper. The single Gur language spoken is Baatọnun, in the extreme Northwest.

The Adamawa–Ubangian languages are spoken between central Nigeria and the Central African Republic. Their westernmost representatives in Nigeria are the Tula-Waja languages. The Kwa languages are represented by the Gun group in the extreme southwest, which is affiliated to the Gbe languages in Benin and Togo.

The classification of the remaining languages is controversial; Joseph Greenberg classified those without noun-classes, such as Yoruba, Igbo, and Ibibio (Efik, Oron, and Annang), as 'Eastern Kwa' and those with classes as 'Benue–Congo'. This was reversed in an influential 1989 publication and reflected on the 1992 map of languages, where all these were considered Benue–Congo. Recent opinion, however, has been to revert to Greenberg's distinction. The literature must thus be read with care and due regard for the date. There are several small language groupings in the Niger Confluence area, notably Ukaan, Akpes, Ayere-Ahan and Ọkọ, whose inclusion in these groupings has never been satisfactorily argued.

Former Eastern Kwa, i.e. West Benue–Congo would then include Igboid, i.e. Igbo language proper, Ukwuani, Ikwerre, Ekpeye etc., Yoruboid, i.e. Yoruba, Itsekiri and Igala, Akokoid (eight small languages in Ondo, Edo and Kogi state), Edoid including Edo (sometimes referred to as) Bini in Edo State, Ibibio-Efik, Idomoid (Idoma) and Nupoid (Nupe) and perhaps include the other languages mentioned above. The Idoma language is classified in the Akweya subgroup of the Idomoid languages of the Volta–Niger family, which include Alago, Agatu, Etulo and Yala languages of Benue, Nasarawa and Northern Cross River states.

East Benue–Congo includes Kainji, Plateau (46 languages, notably Gamai language), Jukunoid, Dakoid and some parts of Cross River. Apart from these, there are numerous Bantoid languages, which are the languages immediately ancestral to Bantu. These include Mambiloid, Ekoid of Cross River State, Bendi, Beboid, Grassfields and Tivoid languages.

Within the Benue-Congo languages, the expansive Bantu language family which covers much of central and southern Africa is represented in Nigeria by; Jarawa with around a quarter million speakers, making it the most spoken Bantu language in the country. Others include Mbula-Bwazza (100,000), Kulung (40,000), Labir (13,000), Bile and a few others.

The geographic distribution of Nigeria's Niger-Congo languages is not limited to the middle east and south-central Nigeria, as migration allows their spread to the linguistically Afro-Asiatic northern regions of Nigeria, as well as throughout West Africa and abroad. Igbo words such as 'unu' for 'you people', 'sooso' for 'only', 'obia' for 'native doctoring', etc. are used in patois of Jamaica and many Central American nations, Yoruba is spoken as a ritual language in cults such as the Santeria in the Caribbean and South-Central America, and the Berbice Dutch language in Surinam is based on an Ijoid language.

Even the above listed linguistic diversity of the Niger–Congo in Nigeria is deceptively limiting, as these languages may further consist of regional dialects that may not be mutually intelligible. As such some languages, particularly those with a large number of speakers, have been standardized and received a romanized orthography. Nearly all languages appear in a Latin alphabet when written.

The Ibibio, Igbo, and Yoruba languages are notable examples of this process. The more historically recent standardization and romanization of Igbo have provoked even more controversy due to its dialectical diversity, but the Central Igbo dialect has gained the widest acceptance as the standard-bearer. Many such as Chinua Achebe have dismissed standardization as colonial and conservative attempts to simplify a complex mosaic of languages.

Such controversies typify inter- and intra-ethnic conflict endemic to post-colonial Nigeria. Also worthy of note is the Enuani dialect, a variation of the Igbo that is spoken among parts of Anioma. The Anioma are the Aniocha, Ndokwa/Ukwuani, Ika and Oshimilli of Delta state. Standard Yoruba came into being due to the work Samuel Crowther, the first African bishop of the Anglican Church and owes most of its lexicon to the dialects spoken in Ọyọ and Ibadan.

Since Standard Yoruba's constitution was determined by a single author rather than by a consensual linguistic policy by all speakers, the Standard has been attacked regarding for failing to include other dialects and spurred debate as to what demarcates "genuine Yoruba". Linguistically speaking, all demonstrate the varying phonological features of the Niger–Congo family to which they belong, these include the use of tone, nasality, and particular consonant and vowel systems; more information is available here.

Branches and locations

Below is a list of major Niger–Congo branches and their primary locations based on Blench (2019).[23]

| Branch | Primary locations |

|---|---|

| Akpes | Akoko North LGA, Ondo State |

| Ayere–Ahan | Akoko North LGA, Ondo State |

| Gbe | Badagry LGA, Lagos State and adjacent areas |

| Yoruboid | South-west, Central, and South-south states of Nigeria |

| Edoid | Rivers, Edo, Ondo, Delta States |

| Akoko | Akoko North LGA, Ondo State |

| Igboid | Anambra, Rivers, Delta States (excluding Igbo proper) |

| Ibibioid | Akwa Ibom State, Cross River States |

| Nupoid | Niger, Kwara, Nasarawa States, Kogi, FCT |

| Oko | Ogori-Magongo LGA, Kogi State |

| Idomoid | Benue, Cross River, Nasarawa States |

| Ukaan | Akoko North LGA, Ondo State |

| Branch | Primary locations |

|---|---|

| Cross River | Cross River, Akwa Ibom, and Rivers States |

| Bendi | Obudu and Ogoja LGAs, Cross River State |

| Mambiloid | Sardauna LGA, Taraba State; Cameroon |

| Dakoid | Mayo Belwa LGA, Taraba State and adjacent areas |

| Jukunoid | Taraba State |

| Yukubenic | Takum LGA, Taraba State |

| Kainji | Kauru LGA, Kaduna State and Bassa LGA, Plateau State; Kainji Lake area |

| Plateau | Plateau, Kaduna, and Nasarawa States |

| Tivoid | Obudu LGA, Cross River State and Sardauna LGA, Taraba State; Cameroon |

| Beboid | Takum LGA, Taraba State; Cameroon |

| Ekoid | Ikom and Ogoja LGAs, Cross River State; Cameroon |

| Grassfields | Sardauna LGA, Taraba State; Cameroon |

| Jarawan (Bantu) | Bauchi, Plateau, Adamawa, and Taraba States |

| Branch | Primary locations |

|---|---|

| Duru (Vere) | Fufore LGA, Adamawa State |

| Leko | Adamawa and Taraba States; Cameroon |

| Mumuye | Taraba State |

| Yendang | Mayo Belwa and Numan LGAs, Adamawa State |

| Waja | Kaltungo and Balanga LGAs, Gombe State |

| Kam | Bali LGA, Taraba State |

| Baa | Numan LGA, Adamawa State |

| Laka | Karim Lamido LGA, Taraba State and Yola LGA, Adamawa State |

| Jenjo | Karim Lamido LGA, Taraba State |

| Bikwin | Karim Lamido LGA, Taraba State |

| Yungur | Song and Guyuk LGAs, Adamawa State |

In addition, Ijaw languages are spoken in Rivers State, Bayelsa State, and other states of the Niger Delta region. Mande languages are spoken in Kebbi State, Niger State, and Kwara State.[23]

In Nigeria, the Nilo-Saharan language family is represented by:

- Saharan languages:

- Songhai languages:

- Zarma (Zabarma) and Dendi in Kebbi State, Zamfara State, Sokoto State, Niger State near the border with the neighbouring countries of Niger and northern Benin, also in Kaduna State, Yobe State and Lagos trading community.

- Central Sudanic languages:

- Lau Laka, a recently discovered Central Sudanic language of Taraba State

French is compulsory in all schools. In January 2016, the Minister for Education Anthony Anwukah announced a wish to make French the second language of business in Nigeria because the majority of African countries are francophone and all of Nigeria's neighbouring countries are francophone.[10][24]

This is a non-exhaustive list of languages spoken in Nigeria.[25][26][27][28]

| S/N | Language | Alternate names | Number of speakers | Native speakers | States spoken in | Current status | Language Varieties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abanyom | Abanyum, Befun, Bofon, Mbofon | 13,000 | Cross River | Active | 2 | |

| Nigerian Pidgin English | Broken. Pidgin | 80,200,000 | All states | ||||

| 2 | Abon | Abong, Abõ, Ba'ban | 1,000 | Taraba | |||

| 3 | Abua | Odual, Abuan | 25,000 | Rivers | |||

| 4 | Abureni | Mini | 4,000 | Bayelsa | |||

| 5 | Achipa | Achipawa | 5,000 | Kebbi | |||

| 6 | Adim | Cross River | |||||

| 7 | Aduge | 30,000 | Anambra | ||||

| 8 | Adun | Cross River | |||||

| 9 | Afade | Affade, Afadeh, Afada, Kotoko, Moga | Borno, Yobe | ||||

| 10 | Afo | Plateau | |||||

| 11 | Afrike | Afrerikpe | 60,000 | Cross River | |||

| 12 | Ajawa | Aja, Ajanci | Bauchi | Extinct | |||

| 13 | Akaju-Ndem | Akajuk | Cross River | Active | |||

| 14 | Akweya-Yachi | Benue | |||||

| 15 | Alago | Arago | Plateau | ||||

| 16 | Amo | ||||||

| 17 | Anaguta | ||||||

| 18 | Annang | 1,000,000 | Akwa Ibom | ||||

| 19 | Angas | 368,000 | Bauchi, Jigawa, Plateau | ||||

| 20 | Ankwei | Plateau | |||||

| 21 | Arabic | Chadian Arabic also known as Shuwa Arabic | 1,000,000 | 100,000 | Borno by Baggara Arabs | ||

| 22 | Anyima | Cross River | |||||

| 23 | Arum | Nasarawa | |||||

| 24 | Attakar | Ataka | Kaduna | ||||

| 25 | Auyoka | Auyokawa, Auyakawa, Awiaka | Jigawa | ||||

| 26 | Awori | Lagos, Ogun | |||||

| 27 | Ayu | Kaduna | |||||

| 28 | Babur | Adamawa, Bomo, Taraba, Yobe | |||||

| 29 | Bachama | Adamawa | |||||

| 30 | Bachere | Cross River | |||||

| 31 | Bada | Plateau | |||||

| 32 | Bade | Yobe | |||||

| 33 | Bakulung | Taraba | |||||

| 34 | Bali | ||||||

| 35 | Bambora | Bambarawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 36 | Bambuko | Taraba | |||||

| 37 | Banda | Bandawa | |||||

| 38 | Banka | Bankalawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 39 | Banso | Panso | Adamawa | ||||

| 40 | Bara | Barawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 41 | Barke | ||||||

| 42 | Baruba | Barba | Niger | ||||

| 43 | Bashiri | Bashirawa | Plateau | ||||

| 44 | Basa | Kaduna, Kogi, Niger, Plateau | |||||

| 45 | Batta | Adamawa | |||||

| 46 | Baushi | Niger | |||||

| 47 | Baya | Adamawa | |||||

| 48 | Bekwarra | Cross River | |||||

| 49 | Bele | Buli, Belewa | Bauchi | ||||

| 50 | Betso | Bete | Taraba | ||||

| 51 | Bette | Cross River | |||||

| 52 | Bilei | Adamawa Rivers | |||||

| 53 | Bille | 40,000 | |||||

| 54 | Bina | Binawa | Kaduna | ||||

| 55 | Bini | Edo | |||||

| 56 | Birom | Plateau | |||||

| 57 | Bobua | Taraba | |||||

| 58 | Boki | Nki | Cross River | ||||

| 59 | Bokkos | Plateau | |||||

| 60 | Boko | Bussawa, Bargawa | Niger | ||||

| 61 | Bole | Bolewa | Bauchi, Yobe | ||||

| 62 | Botlere | Adamawa | |||||

| 63 | Boma | Bomawa, Burmano | Bauchi | ||||

| 64 | Bomboro | ||||||

| 65 | Buduma | Borno, Niger | |||||

| 66 | Buji | Plateau | |||||

| 67 | Buli | Bauchi | |||||

| 68 | Bunu | Kogi | |||||

| 69 | Bura | Bura-Pabir | Borno, Adamawa, Yobe | ||||

| 70 | Burak | Bauchi | |||||

| 71 | Burma | Burmawa | Plateau | ||||

| 72 | Buru | Yobe | |||||

| 73 | Buta | Butawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 74 | Bwall | Plateau | |||||

| 75 | Bwatiye | Adamawa | |||||

| 76 | Bwazza | ||||||

| 77 | Challa | Plateau | |||||

| 78 | Chama | Chamawa Fitilai | Bauchi | ||||

| 79 | Chamba | Taraba | |||||

| 80 | Chamo | Bauchi | |||||

| 81 | Cibak | Chibbak, Chibok | Borno | ||||

| 82 | Chinine | Borno | |||||

| 83 | Chip | Plateau | |||||

| 84 | Chokobo | ||||||

| 85 | Chukkol | Taraba | |||||

| 86 | Cipu | Western Acipa | 20,000 | Kebbi, Niger | |||

| 87 | Daba | Adamawa | |||||

| 88 | Dadiya | Bauchi | |||||

| 89 | Daka | Adamawa | |||||

| 90 | Dakarkari | Niger, Kebbi | |||||

| 91 | Danda | Dandawa | Kebbi | ||||

| 92 | Dangsa | Taraba | |||||

| 93 | Daza | Dere, Derewa | Bauchi | ||||

| 94 | Degema | Rivers | |||||

| 95 | Deno | Denawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 96 | Dghwede | 30,000 | Borno | ||||

| 97 | Diba | Taraba | |||||

| 98 | Doemak | Dumuk | Plateau | ||||

| 99 | Duguri | Bauchi | |||||

| 100 | Duka | Dukawa | Kebbi | ||||

| 101 | Duma | Dumawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 102 | Ebana | Ebani | Rivers | ||||

| 103 | Ebirra | Igbirra | 1,000,000 | Edo, Kogi, Ondo | |||

| 104 | Ebu | Edo, Kogi | |||||

| 105 | Efik | Cross River | |||||

| 106 | Egbema | Rivers, Imo | |||||

| 107 | Eggon | Plateau | |||||

| 108 | Egun | Gùn | Lagos, Ogun | ||||

| 109 | Ejagham | Jagham | Cross River | ||||

| 110 | Ekajuk | ||||||

| 111 | Eket | Akwa Ibom | |||||

| 112 | Ekoi | Cross River | |||||

| 113 | Ekpeye | Ekpe ye | Rivers | ||||

| 114 | Engenni | Ngene | |||||

| 115 | Epie | ||||||

| 116 | English | 178,000,000 | 40,000,000 | 4 | |||

| 117 | Esan | Ishan | Edo | ||||

| 118 | Etche | Rivers | |||||

| 119 | Etolu | Etilo | Benue | ||||

| 120 | Etsako | Afenmai | Edo | ||||

| 121 | Etung | Cross River | |||||

| 122 | Etuno | Edo | |||||

| 123 | Falli | Adamawa | |||||

| 124 | French | 1,000,000 | 200,000 | Bordering states of Nigeria | |||

| 125 | Fula | Fulani, Fulbe, Fulfulde | 15,000,000 | 12,000,000 | Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Niger, Sokoto, Taraba, Yobe | 7 | |

| 126 | Fyam | Fyem | Plateau | ||||

| 127 | Fyer | Fer | |||||

| 128 | Ga’anda | Adamawa | |||||

| 129 | Gade | Niger | |||||

| 130 | Galambi | Bauchi | |||||

| 131 | Gamergu | Mulgwa, Malgo, Malgwa | Borno | ||||

| 132 | Ganawuri | Qanawuri | Plateau | ||||

| 133 | Gavako | Borno | |||||

| 134 | Gbedde | Kogi | |||||

| 135 | Gbo | Agbo, Legbo | Cross River | ||||

| 136 | Gengle | Taraba | |||||

| 137 | Geji | Bauchi | |||||

| 138 | Gera | Gere, Gerawa | |||||

| 139 | Geruma | Gerumawa | Bauchi, Plateau | ||||

| 140 | Gingwak | Bauchi | |||||

| 141 | Gira | Adamawa | |||||

| 142 | Gizigz | ||||||

| 143 | Goernai | Kaduna | |||||

| 144 | Gong | 100,000 | Plateau | ||||

| 145 | Gokana | Kana | Rivers | ||||

| 146 | Gombi | Adamawa | |||||

| 147 | Gornun | Gmun | Taraba | ||||

| 148 | Gonia | ||||||

| 149 | Gubi | Gubawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 150 | Gude | Adamawa | |||||

| 151 | Gudu | ||||||

| 152 | Gure | Kaduna | |||||

| 153 | Gurmana | Niger | |||||

| 154 | Gururntum | Bauchi | |||||

| 155 | Gusu | Plateau | |||||

| 156 | Gwa | Gurawa | Adamawa | ||||

| 157 | Gwamba | ||||||

| 158 | Gwandara | Kaduna, Niger, Plateau | |||||

| 159 | Gwari | Gbari | Kaduna, Niger, FCT, Nasarawa,Kogi | ||||

| 160 | Gwom | Taraba | |||||

| 161 | Gwoza | 40,000 | Borno | ||||

| 162 | Gyem | Bauchi | |||||

| 163 | Hausa | 80,000,000 | 57,000,000 | Bauchi, Borno, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Kastina, Kebbi, Niger, Taraba, Sokoto, Zamfara | 9 | ||

| 164 | Humono | Kohumono | Cross River | ||||

| 165 | Holma | Adamawa | |||||

| 166 | Hona | ||||||

| 167 | Hyam | Ham, Jaba, Jabba | Kaduna | ||||

| 168 | Ibeno | Akwa Ibom | |||||

| 169 | Ibibio | 12,000,000 | 9,000,000 | Akwa Ibom, Cross River | |||

| 170 | Ichen | Adamawa | |||||

| 171 | Idoma | Benue, Taraba | |||||

| 172 | Igala | Kogi, Benue, Anambra | |||||

| 173 | Igbo | 42,000,000 | 41,000,000 | Abia, Anambra, Delta, Ebonyi, Enugu, Imo, Rivers | 3 | ||

| 174 | Igede | Egede | Benue | ||||

| 175 | Ijaw | Bayelsa, Rivers | Engenni | Ngene | |||

| 176 | Ijumu | Kogi | |||||

| 176 | Ika | Delta | |||||

| 177 | Ikorn | Cross River | |||||

| 178 | Irigwe | Plateau | |||||

| 179 | Isoko | Delta | |||||

| 180 | Isekiri | Itsekiri | 1,000,000 | ||||

| 181 | Iyala | Iyalla | Cross River | ||||

| 182 | Izere | Izarek, Fizere, Fezere, Feserek, Afizarek, Afizare, Afusare, Jari, Jarawa, Jarawan Dutse, Hill Jarawa, Jos-Zarazon. | 100,000 | Plateau | |||

| 183 | Izondjo | Bayelsa, Delta, Ondo, Rivers | |||||

| 184 | Jahuna | Jahunawa | Taraba | ||||

| 185 | Jaku | Bauchi | |||||

| 186 | Jara | Jaar, Jarawa, Jarawa-Dutse | |||||

| 187 | Jere | Jare, Jera, Jera, Jerawa | Bauchi, Plateau | ||||

| 188 | Jero | Taraba | |||||

| 189 | Jibu | Adamawa | |||||

| 190 | Jidda-Abu | Plateau | |||||

| 191 | Jimbin | Jimbinawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 192 | Jirai | Adamawa | |||||

| 193 | Jju | Kaje, Kache | Kaduna | ||||

| 194 | Jonjo | Jenjo | Taraba | ||||

| 195 | Jukun | Bauchi, Benue, Taraba, Plateau | |||||

| 196 | Kaba | Kabawa | Taraba | ||||

| 197 | Kadara | Ajuah, Ajure, Adaa, Adara, Azuwa, Ajuwa, Azuwa,[citation needed] Eda | Kaduna,[29] Niger[30] | ||||

| 198 | Kafanchan | Kaduna | |||||

| 199 | Kagoro | ||||||

| 20 | Kajuru | Kajurawa | |||||

| 201 | Kaka | Manenguba | Adamawa | ||||

| 202 | Kamaku | Karnukawa | Kaduna, Kebbi, Niger | ||||

| 203 | Kambari | Kebbi, Niger | |||||

| 204 | Kamwe | Adamawa, Borno and Republic of Cameroon | Active[31] | ||||

| 205 | Kamo | Bauchi | Active | ||||

| 206 | Kanakuru | Dera | Adamawa, Borno | ||||

| 207 | Kanembu | Borno | |||||

| 208 | Kanikon | Kaduna | |||||

| 209 | Kantana | Plateau | |||||

| 210 | Kanufi | Kaduna[32] | |||||

| 211 | Kanuri | Borno, Kaduna, Adamawa, Kano, Niger, Jigawa, Plateau, Taraba, Yobe | |||||

| 212 | Karai-Karai (language) | Karaikarai, Karekare | Bauchi, Yobe | ||||

| 213 | Karimjo | Taraba | |||||

| 214 | Kariya | Bauchi | |||||

| 215 | Katab | Kataf | Kaduna | ||||

| 216 | Kenern | Koenoem | Plateau | ||||

| 217 | Kenton | Taraba | |||||

| 218 | Kiballo | Kiwollo | Kaduna | ||||

| 219 | Kilba | Adamawa | |||||

| 220 | Kirfi | Kirfawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 221 | Koma | Taraba | |||||

| 222 | Kona | ||||||

| 223 | Koro | Kwaro | Kaduna, Niger, Nasarawa | ||||

| 224 | Kubi | Kubawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 225 | Kudachano | Kudawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 226 | Kugama | Taraba | |||||

| 227 | Kulere | Kaler | Plateau | ||||

| 228 | Kunini | Taraba | |||||

| 229 | Kurama | Jigawa, Kaduna, Niger, Plateau | |||||

| 230 | Kurdul | Adamawa | |||||

| 231 | Kushi | Bauchi | |||||

| 232 | Kuteb | Taraba | |||||

| 233 | Kutin | ||||||

| 234 | Kwah | Baa | 18,000 | Adamawa | |||

| 235 | Kwalla | Plateau | |||||

| 236 | Kwami | Kwom | Bauchi | ||||

| 237 | Kwanchi | Taraba | |||||

| 238 | Kwanka | Kwankwa | Bauchi, Plateau | ||||

| 239 | Kwaro | Plateau | |||||

| 240 | Kwato | ||||||

| 241 | Kyenga | Kengawa | Sokoto | ||||

| 242 | Laaru | Larawa | Niger | ||||

| 243 | Lakka | Adamawa | |||||

| 244 | Lala | ||||||

| 245 | Lama | Taraba | |||||

| 246 | Lamja | ||||||

| 247 | Lau | ||||||

| 248 | Ubbo | Adamawa | |||||

| 249 | Limono | Bauchi, Plateau | |||||

| 250 | Lopa | Lupa, Lopawa | Niger | ||||

| 251 | Longuda | Lunguda | Adamawa, Bauchi | ||||

| 252 | Mabo | Plateau | |||||

| 253 | Mada | Kaduna, Plateau | |||||

| 254 | Mama | Plateau | |||||

| 255 | Mambilla | Adamawa | |||||

| 256 | Manchok | Kaduna | |||||

| 257 | Mandara | Wandala | Borno | ||||

| 258 | Manga | Mangawa | Yobe | ||||

| 259 | Margi | Adamawa, Borno | |||||

| 260 | Matakarn | Adamawa | |||||

| 261 | Mbembe | Cross River, Enugu | |||||

| 262 | Mbol | Adamawa | |||||

| 263 | Mbube | Cross River | |||||

| 264 | Mbula | Adamawa | |||||

| 265 | Mbum | Taraba | |||||

| 266 | Memyang | Meryan | Plateau | ||||

| 267 | Miango | ||||||

| 268 | Miligili | Migili | |||||

| 269 | Miya | Miyawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 270 | Mobber | Borno | |||||

| 271 | Montol | Plateau | |||||

| 272 | Moruwa | Moro’a, Morwa | Kaduna | ||||

| 273 | Muchaila | Adamawa | |||||

| 274 | Mumuye | Taraba | |||||

| 275 | Mundang | Adamawa | |||||

| 276 | Mupun | 1,000,000 | Plateau | ||||

| 278 | Mushere | ||||||

| 279 | Mwahavul | Mwaghavul | |||||

| 280 | Ndoro | Taraba | |||||

| 281 | Ngamo | Bauchi, Yobe | |||||

| 282 | Ngizim | Yobe | |||||

| 283 | Ngweshe | Ndhang, Ngoshe-Ndhang | Adamawa, Borno | ||||

| 284 | Ningi | Ningawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 285 | Ninzam | Ninzo | Kaduna, Plateau | ||||

| 286 | Njayi | Adamawa | |||||

| 287 | Nkim | Cross River | |||||

| 288 | Nkum | ||||||

| 289 | Nokere | Nakere | Plateau | ||||

| 290 | Nsukka | Enugu State and some parts of Kogi state | |||||

| 291 | Nunku | Kaduna, Plateau | |||||

| 292 | Nupe | Niger, Kwara, Kogi, FCT | |||||

| 293 | Nyandang | Taraba | |||||

| 294 | Obolo | Andoni | Akwa Ibom, Rivers | ||||

| 295 | Ogba | Ogba | 1000+ | Rivers | |||

| 296 | Ogbia | Bayelsa | |||||

| 297 | Ofutop | Ofutop (okangha(2) | 5,000 | 4,000 | Ikom, Okuni, Cross River | ||

| 298 | Ogori | Kwara | |||||

| 299 | Okobo | Okkobor | Akwa Ibom | ||||

| 300 | Okpamheri | Edo | |||||

| 301 | Okpe | Okpe | 1,000,000 | Delta | |||

| 302 | Olulumo | Cross River | |||||

| 302 | Oro | Oron | 1,000,000 | Akwa Ibom | |||

| 303 | Owan | Edo | |||||

| 304 | Owe | Kwara | |||||

| 305 | Oworo | ||||||

| 306 | Pa’a | Pa’awa, Afawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 307 | Pai | Plateau | |||||

| 308 | Panyam | Taraba | |||||

| 309 | Pero | Bauchi | |||||

| 310 | Pire | Adamawa | |||||

| 311 | Pkanzom | Taraba | |||||

| 312 | Poll | ||||||

| 313 | Polchi Habe | Bauchi | |||||

| 314 | Pongo | Pongu | Niger | ||||

| 315 | Potopo | Taraba | |||||

| 315 | Pyapun | Piapung | Plateau | ||||

| 317 | Qua | Cross River | |||||

| 318 | Rebina | Rebinawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 319 | Reshe | Kebbi, Niger | |||||

| 320 | Rindire | Rendre | Plateau | ||||

| 321 | Rishuwa | Kaduna | |||||

| 322 | Ron | Plateau | |||||

| 323 | Rubu | Niger | |||||

| 324 | Rukuba | Plateau | |||||

| 325 | Rumada | Kaduna | |||||

| 326 | Rumaya | ||||||

| 327 | Sakbe | Taraba | |||||

| 328 | Sanga | Bauchi | |||||

| 329 | Sate | Taraba | |||||

| 330 | Saya | Sayawa, Za’ar | Bauchi, Plateau, Kaduna, Abuja, Niger, Kogi | ||||

| 331 | Segidi | Sigidawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 332 | Shanga | Shangawa | Sokoto | ||||

| 333 | Shangawa | Shangau | Plateau | ||||

| 334 | Shan-Shan | Plateau | |||||

| 335 | Shira | Shirawa | Kano | ||||

| 336 | Shomo | Taraba | |||||

| 337 | Shuwa | Adamawa, Borno | |||||

| 338 | Sikdi | Plateau | |||||

| 339 | Siri | Sirawa | Bauchi | ||||

| 340 | Srubu | Surubu | Kaduna | ||||

| 341 | Sukur | Adamawa | |||||

| 342 | Sura | Plateau | |||||

| 343 | Tangale | Bauchi | |||||

| 344 | Tarok | Plateau, Taraba | |||||

| 345 | Teme | Adamawa | |||||

| 346 | Tera | Terawa | Bauchi, Bomo | ||||

| 347 | Teshena | Teshenawa | Kano | ||||

| 348 | Tigon | Adamawa | |||||

| 349 | Tikar | Taraba | |||||

| 350 | Tiv | 5,000,000 | Benue, Plateau,adamawa, Taraba, Nasarawa | 2 | |||

| 351 | Tula | Bauchi | |||||

| 352 | Tur | Adamawa | |||||

| 353 | Ufia | Benue | |||||

| 354 | Ukelle | Kele, Kukelle | Cross River | ||||

| 355 | Ukwani | Kwale,Aboh | Delta | ||||

| 356 | Uncinda | Kaduna, Kebbi, Niger, Sokoto | |||||

| 357 | Uneme | Ineme | Edo | ||||

| 358 | Ura | Ula | Niger | ||||

| 359 | Urhobo | 1,000,000 | Delta | ||||

| 360 | Utonkong | Benue | |||||

| 361 | Uvwie | 100,000 | Delta | ||||

| 362 | Uyanga | Cross River | |||||

| 363 | Vemgo | Adamawa | |||||

| 364 | Verre | ||||||

| 365 | Vommi | Taraba | |||||

| 366 | Wagga | Adamawa | |||||

| 367 | Waja | Bauchi | |||||

| 368 | Waka | Taraba | |||||

| 369 | Warja | Jigawa | |||||

| 370 | Warji | Bauchi | |||||

| 371 | Wula | Adamawa | |||||

| 372 | Wurbo | ||||||

| 373 | Wurkun | Taraba | |||||

| 374 | Yache | Cross River | |||||

| 375 | Yagba | Kwara | |||||

| 376 | Yakurr | Yako | Cross River | ||||

| 377 | Yalla | Benue | |||||

| 378 | Yandang | Taraba | |||||

| 379 | Yergan | Yergum | Plateau | ||||

| 380 | Yoruba | 54,000,000 | 48,000,000 | Kwara, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Oyo, Osun, Ekiti, Kogi, Edo | 2 | ||

| 381 | Yott | Taraba | |||||

| 382 | Yumu | Niger | |||||

| 383 | Yungur | Adamawa | |||||

| 384 | Yuom | 250,000 | Plateau | ||||

| 385 | Zabara | Niger | |||||

| 386 | Zaranda | Bauchi | |||||

| 387 | Zarma | Dyerma, Dyarma, Dyabarma, Zabarma, Adzerma, Djerma, Zarbarma, Zerma, Zarmawa | Kebbi, Sokoto, Zamfara, Niger State, Yobe, Kaduna, Lagos | ||||

| 388 | Zayam | Zeam | Bauchi | ||||

| 389 | Zul | Zulawa |

- "Language data for Nigeria". Translators without Borders. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- Blench, Roger (2014). An Atlas Of Nigerian Languages. Oxford: Kay Williamson Educational Foundation.

- "Language data for Nigeria". Translators without Borders. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- "Nigeria: languages by number of speakers 2021". Statista. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- "Africa: Nigeria". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2020-06-21.

- Adeleke, Dr Wale. "Languages of Nigeria - Regions". NaijaSky. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- "Nigeria: languages by number of speakers 2021". Statista. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- Obiukwu, Onyedimmakachukwu. "Nigeria has a massive, largely overlooked, language crisis". Ventures Africa. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- Osoba, Joseph Babasola; Alebiosu, Tajudeen Afolabi (2016). "Language Preference as a Precursor to Displacement and Extinction in Nigeria: The Roles of English Language and Nigerian Pidgin". Journal of Universal Language. 17 (2): 111–143. doi:10.22425/jul.2016.17.2.111. ISSN 2508-5344.

- Ali, Salaudeen. "Effect of choosing common lingua franca in Nigeria by Salaudeen Ali".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Language data for Nigeria". Translators without Borders. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- Osoba, Joseph Babasola (2014-03-26). "The Use of Nigerian Pidgin in Media Adverts". International Journal of English Linguistics. 4 (2). doi:10.5539/ijel.v4n2p26. ISSN 1923-8703.

- Osoba, Joseph Babasola (2014-03-31). "The Use of Nigerian Pidgin in Political Jingles". Journal of Universal Language. 15 (1): 105–127. doi:10.22425/jul.2014.15.1.105. ISSN 1598-6381.

- Douglas, B. 2012. The Status of Nigerian Pidgin and Other Indigenous Languages in Bayelsa State Tertiary Institutions. Unpublished M.A. Thesis, Obafemi Awolowo University. In: Osoba, Joseph Babasola; Alebiosu, Tajudeen Afolabi (2016). "Language Preference as a Precursor to Displacement and Extinction in Nigeria: The Roles of English Language and Nigerian Pidgin". Journal of Universal Language. 17 (2): 111–143. doi:10.22425/jul.2016.17.2.111. ISSN 2508-5344.

- "Afro-Asiatic languages | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- "History – Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Nigeria". Retrieved 2022-11-23.

- Aderibigbe, Victor. "A CRITIQUE OF THE SOKOTO JIHAD IN HAUSALAND IN THE OPENING DECADE OF THE 19TH CENTURY".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Ochonu, Moses (2015). "Caliphate Expansion and Sociopolitical Change in Nineteenth-Century Lower Benue Hinterlands". Journal of West African History. 1 (1): 133–178. doi:10.14321/jwestafrihist.1.1.0133. ISSN 2327-1868. JSTOR 10.14321/jwestafrihist.1.1.0133. S2CID 128410954.

- "Niger-Congo languages « Sorosoro". Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- Blench, Roger (2019). An Atlas of Nigerian Languages (4th ed.). Cambridge: Kay Williamson Educational Foundation.

- "FG declares French compulsory for all students | The Nation Newspaper". The Nation Newspaper. 2016-01-31. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- Blench, Roger (2014). An Atlas Of Nigerian Languages. Cambridge: Kay Williamson Educational Foundation.

- Crozier, David Henry; Blench, Roger (1992). An Index of Nigerian languages. Dallas: Summer Inst of Linguistics. ISBN 9780883126110.

- "Ethnologue 15 report for Nigeria". archive.ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- "A Summary of a Sociolinguistic Survey of the Adara of Kaduna and Niger States, Nigeria". SIL International. November 24, 2014.

- Mbeke-Ekanem, Tom (May 19, 2000). Beyond the Execution: Understanding the Ethnic and Military Politics in Nigeria. Writer's Showcase. ISBN 9780595092802 – via Google Books.

- Kwache,IY (2016)Kamwe People of Northern Nigeria: Origin, History and Culture

- Olson, James Stuart; Meur, Charles (May 19, 1996). The Peoples of Africa: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313279188 – via Google Books.

- Crozier, David & Blench, Roger (1992) An Index of Nigerian Languages (2nd edition). Dallas: SIL.mbembe language in cross river

- Blench, Roger (1998) 'The Status of the Languages of Central Nigeria', in Brenzinger, M. (ed.) Endangered languages in Africa. Köln: Köppe Verlag, 187–206. online version

- Blench, Roger (2002) Research on Minority Languages in Nigeria in 2001. Ogmios.

- Blench, Roger (n.d.) Atlas of Nigerian Languages, ed. III (revised and amended edition of Crozier & Blench 1992)

- Kwache, Iliya Yame (2016) Kamwe People of Northern Nigeria :Origin, History and Culture

- Chigudu, Theophilus Tanko (2017); Indigenous peoples of North clCentral Nigeria Area: an endangered race.

- Blench, Roger (2019). An Atlas of Nigerian Languages (4th ed.). Cambridge: Kay Williamson Educational Foundation.

- Emenanjo, E. N. (2019). Four Decades in the Study of Nigerian Languages and Linguistics: A Festschrift for KayWilliamson.

- Lamle, Elias Nankap, Coprreality and Dwelling spaces in Tarokland. NBTT Press. Jos Nigeria in "Ngappak" journal of the Tarok Nation 2005