Demographics_of_Mexico

With a population of about 129 million in 2022,[4] Mexico is the 10th most populated country in the world. It is the largest Spanish-speaking country in the world and the third-most populous country in the Americas after the United States and Brazil.[5] Throughout most of the 20th century Mexico's population was characterized by rapid growth. Although this tendency has been reversed and average annual population growth over the last five years was less than 1%, the demographic transition is still in progress; Mexico still has a large youth cohort. The most populous city in the country is the capital, Mexico City, with a population of 8.9 million (2016), and its metropolitan area is also the most populated with 20.1 million (2010). Approximately 50% of the population lives in one of the 55 large metropolitan areas in the country. In total, about 78.84% of the population of the country lives in urban areas, and only about 21.16% in rural ones.

| Demographics of Mexico | |

|---|---|

Mexico population pyramid in 2020 | |

| Population | 129,150,971[1] |

| Growth rate | 1.9% (2015)[2] |

| Birth rate | 14.8 births/1,000 population (2022 est.) |

| Death rate | 6.5 deaths/1,000 population (2022 est.) |

| Life expectancy | 76.66 years |

| • male | 73.84 years |

| • female | 79.63 years (2012 est.) |

| Fertility rate | 1.63 children born/woman (2020 est.) |

| Infant mortality rate | 16.77 deaths/1,000 live births |

| Net migration rate | −1.64 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2014 est.)[3] |

| Age structure | |

| 0–14 years | 25.2% (male 16,084,833/ female 15,670,451) |

| 15–64 years | 66.4% (male 40,506,343/ female 43,157,097) |

| 65 and over | 8.4% (male 4,746,020/ female 5,575,894) (2020 est.) |

| Sex ratio | |

| Total | 0.96 male(s)/female (2011 est.) |

| At birth | 1.04 male(s)/female |

| Under 15 | 1.05 male(s)/female |

| 15–64 years | 0.94 male(s)/female |

| 65 and over | 0.81 male(s)/female |

| Nationality | |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Language | |

| Spoken | Spanish, Zapotec, Nahuatl, Mixtec, Purépecha, English, Tzeltal, German, French, Chinese, Italian, and many others are also spoken varying by region |

Demographic censuses are performed by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informatica. The National Population Council (CONAPO) is an institution under the Ministry of Interior in charge of the analysis and research of population dynamics. The National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CDI), also undertakes research and analysis of the sociodemographic and linguistic indicators of the indigenous peoples.

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1865 | 8,259,080[6] | — |

| 1895 | 12,700,294 | +1.44% |

| 1900 | 13,607,272 | +1.39% |

| 1910 | 15,160,369 | +1.09% |

| 1921 | 14,334,780 | −0.51% |

| 1930 | 16,552,722 | +1.61% |

| 1940 | 19,653,552 | +1.73% |

| 1950 | 25,791,017 | +2.75% |

| 1960 | 34,923,129 | +3.08% |

| 1970 | 48,225,238 | +3.28% |

| 1980 | 66,846,833 | +3.32% |

| 1990 | 81,249,645 | +1.97% |

| 2000 | 97,483,412 | +1.84% |

| 2010 | 112,336,538 | +1.43% |

| 2020 | 126,014,024 | +1.16% |

| Source: INEGI | ||

Estimates vary for the Pre-Columbian population of Mexico from 1.5 million to 21 million,[7] but the most accepted figure is about 11 million people, including the population of the Aztec Empire which is estimated at 5 to 6 million people.[8] The population was estimated to have been 1-2 million in 1600 and in 1700, the population was estimated to be around 4 million. In 1900, the Mexican population was 13.6 million.[9] During the period of economic prosperity that was dubbed by economists as the "Mexican Miracle", the government invested in efficient social programs that reduced the infant mortality rate and increased life expectancy. These measures jointly led to an intense demographic increase between 1930 and 1980. The population's annual growth rate has been reduced from a 3.5% peak in 1965 to 0.99% in 2005. While Mexico is now transitioning to the third phase of demographic transition, close to 50% of the population in 2009 was 25 years old or younger.[10] Fertility rates have also decreased from 5.7 children per woman in 1976 to 2.2 in 2006.[11] After decades of the gap narrowing, in 2020 the fertility rate in Mexico fell below the United States for the first time falling 22% in 2020 and a further 10.5% in the first half of 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[12]

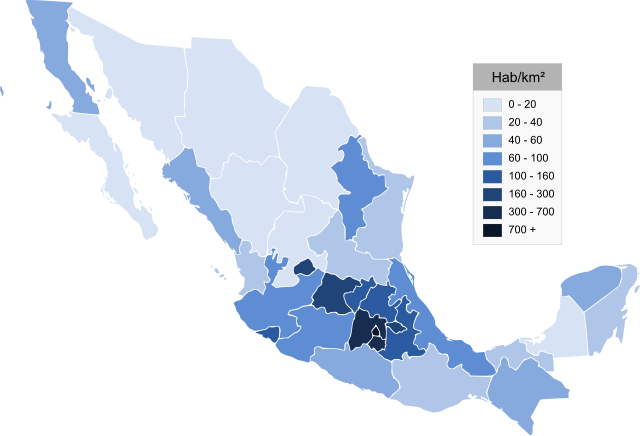

The average annual population growth rate of Mexico City was 0.2%. The state with the lowest population growth rate over the same period was Michoacán (-0.1%), whereas the states with the highest population growth rates were Quintana Roo (4.7%) and Baja California Sur (3.4%),[13] both of which are two of the least populous states and the last to be admitted to the Union in the 1970s. The average annual net migration rate of Mexico City over the same period was negative and the lowest of all political divisions of Mexico, whereas the states with the highest net migration rate were Quintana Roo (2.7), Baja California (1.8) and Baja California Sur (1.6).[14] While the national annual growth rate was still positive (1.0%) in the early years of the 2000s, the national net migration rate was negative (-4.75/1000 inhabitants), given the former strong flow of immigrants to the United States; an estimated 5.3 million undocumented Mexican immigrants lived in the United States in 2004[15] and 18.2 million American citizens in the 2000 Census declared having Mexican ancestry.[16] However, as of recent years in the 2010s, the net migration rate reached 0, given the strong economy of Mexico, changes in US Immigration Policy & Enforcement, US Legislative and CFR-8 decisions, plus the (then) slowly recovering US economy, causing many of its former residents to return. The Mexican government projects[17] that the Mexican population will grow to about 123 million by 2042 and then start declining slowly. Assumptions underlying this projection include fertility stabilizing at 1.85 children per woman and continued high net emigration (slowly decreasing from 583,000 in 2005 to 393,000 in 2050).

The states and Mexico City that make up the Mexican federation are collectively called "federal entities". The five most populous federal entities in 2005 were the State of Mexico (14.4 million), Mexico City (8.7 million), Veracruz (7.1 million), Jalisco (6.7 million) and Puebla (5.4 million), which collectively contain 40.7% of the national population. Mexico City, being coextensive with the Mexico City, is the most populous city in the country, while Greater Mexico City, that includes the adjacent municipalities that comprise a metropolitan area, is estimated to be the second most populous in the world (after Tokyo), according to the UN Urbanization Report.

Intense population growth in the northern states, especially along the US-Mexican border, changed the country's demographic profile in the second half of the 20th century, as the 1967 US-Mexico maquiladora agreement through which all products manufactured in the border cities could be imported duty-free to the US. Since the adoption of NAFTA in 1994, however, which allows all products to be imported duty-free regardless of their place of origin within Mexico, the non-border maquiladora share of exports has increased while that of border cities has decreased.[18] This has led to decentralization and rapid economic growth in Mexican states (and cities), such as Quintana Roo (Cancun), Baja California Sur (La Paz), Nuevo León (Monterrey), Querétaro, and Aguascalientes. The population of each of these five states grew by more than one-third from 2000 to 2015, while the whole of Mexico grew by 22.6% in this period.

UN estimates

According to the 2012 revision of the World Population Prospects, the total population was 117,886,000 in 2010, compared to only 28,296,000 in 1950. The proportion of children below the age of 15 in 2010 was 30%, 64% of the population was between 15 and 65 years of age, and 6% was 65 years or older.[19]

| Total population (x 1000) |

Proportion aged 0–14 (%) |

Proportion aged 15–64 (%) |

Proportion aged 65+ (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 28 296 | 42.5 | 54.1 | 3.5 |

| 1955 | 33 401 | 44.5 | 52.2 | 3.3 |

| 1960 | 38 677 | 45.9 | 50.8 | 3.4 |

| 1965 | 45 339 | 46.8 | 49.6 | 3.5 |

| 1970 | 52 988 | 46.6 | 49.7 | 3.7 |

| 1975 | 61 708 | 46.2 | 50.1 | 3.7 |

| 1980 | 70 353 | 44.7 | 51.5 | 3.8 |

| 1985 | 77 859 | 42.1 | 53.9 | 3.9 |

| 1990 | 86 077 | 38.5 | 57.2 | 4.3 |

| 1995 | 95 393 | 35.9 | 59.6 | 4.5 |

| 2000 | 103 874 | 34.1 | 61.0 | 4.9 |

| 2005 | 110 732 | 32.3 | 62.4 | 5.3 |

| 2010 | 117 886 | 30.0 | 64.0 | 6.0 |

| 2015 | 127 017 | 27.6 | 65.9 | 6.5 |

| 2020 | 134 837 | 25.6 | 66.9 | 7.6 |

Structure of the population

Population by Sex and Age Group (Census 12.VI.2010) (Including an estimation of 1 334 585 persons corresponding to 448 195 housing units without information of the occupants.):[20]

| Age Group | Male | Female | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 54 855 231 | 57 481 307 | 112 336 538 | 100 |

| 0–4 | 5 346 943 | 5 181 379 | 10 528 322 | 9.37 |

| 5–9 | 5 604 175 | 5 443 362 | 11 047 537 | 9.83 |

| 10–14 | 5 547 613 | 5 392 324 | 10 939 937 | 9.74 |

| 15–19 | 5 520 121 | 5 505 991 | 11 026 112 | 9.82 |

| 20–24 | 4 813 204 | 5 079 067 | 9 892 271 | 8.81 |

| 25–29 | 4 205 975 | 4 582 202 | 8 788 177 | 7.82 |

| 30–34 | 4 026 031 | 4 444 767 | 8 470 798 | 7.54 |

| 35–39 | 3 964 738 | 4 328 249 | 8 292 987 | 7.38 |

| 40–44 | 3 350 322 | 3 658 904 | 7 009 226 | 6.24 |

| 45–49 | 2 824 364 | 3 104 366 | 5 928 730 | 5.28 |

| 50–54 | 2 402 451 | 2 661 840 | 5 064 291 | 4.51 |

| 55–59 | 1 869 537 | 2 025 828 | 3 895 365 | 3.47 |

| 60–64 | 1 476 667 | 1 639 799 | 3 116 466 | 2.77 |

| 65–69 | 1 095 273 | 1 221 992 | 2 317 265 | 2.06 |

| 70–74 | 873 893 | 1 000 041 | 1 873 934 | 1.67 |

| 75–79 | 579 689 | 665 794 | 1 245 483 | 1.11 |

| 80–84 | 355 277 | 443 659 | 798 936 | 0.71 |

| 85–89 | 197 461 | 256 703 | 454 164 | 0.40 |

| 90–94 | 68 130 | 96 794 | 164 924 | 0.15 |

| 95–99 | 25 920 | 39 812 | 65 732 | 0.06 |

| 100+ | 7 228 | 11 247 | 18 475 | 0.02 |

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | Percent |

| 0–14 | 16 498 731 | 16 017 065 | 32 515 796 | 28.94 |

| 15–64 | 34 453 410 | 37 031 013 | 71 484 423 | 63.63 |

| 65+ | 3 202 871 | 3 736 042 | 6 938 913 | 6.18 |

| unknown | 700 219 | 697 187 | 1 397 406 | 1.24 |

Population by Sex and Age Group (Census 15.III.2020) (Including an estimation of 6 337 751 persons corresponding to 1 588 422 housing units without information of the occupants.):[21]

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 61 473 390 | 64 540 634 | 126 014 024 | 100 |

| 0–4 | 5 077 482 | 4 969 883 | 10 047 365 | 7.97 |

| 5–9 | 5 453 091 | 5 311 288 | 10 764 379 | 8.54 |

| 10–14 | 5 554 260 | 5 389 280 | 10 943 540 | 8.68 |

| 15–19 | 5 462 150 | 5 344 540 | 10 806 690 | 8.57 |

| 20–24 | 5 165 884 | 5 256 211 | 10 422 095 | 8.27 |

| 25–29 | 4 861 404 | 5 131 597 | 9 993 001 | 7.93 |

| 30–34 | 4 527 726 | 4 893 101 | 9 420 827 | 7.47 |

| 35–39 | 4 331 530 | 4 668 746 | 9 020 276 | 7.15 |

| 40–44 | 4 062 304 | 4 441 282 | 8 503 586 | 6.74 |

| 45–49 | 3 812 344 | 4 130 069 | 7 942 413 | 6.30 |

| 50–54 | 3 332 163 | 3 705 360 | 7 037 532 | 5.58 |

| 55–59 | 2 692 976 | 3 002 982 | 5 695 958 | 4.52 |

| 60–64 | 2 257 862 | 2 563 200 | 4 821 062 | 3.82 |

| 65–69 | 1 706 850 | 1 938 227 | 3 645 077 | 2.89 |

| 70–74 | 1 233 492 | 1 413 848 | 2 647 340 | 2.10 |

| 75–79 | 847 898 | 966 684 | 1 814 582 | 1.43 |

| 80–84 | 523 812 | 651 552 | 1 175 364 | 0.93 |

| 85+ | 433 968 | 605 583 | 1 039 551 | 0.82 |

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | Percent |

| 0–14 | 16 084 833 | 15 670 451 | 31 755 284 | 25.20 |

| 15–64 | 40 506 343 | 43 157 097 | 83 663 440 | 66.39 |

| 65+ | 4 746 020 | 5 575 894 | 10 321 914 | 8.19 |

| unknown | 136 194 | 137 192 | 273 386 | 0.22 |

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Registered births and deaths

Source: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI)[22][23]

| Average population[24] | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) | Crude death rate (per 1000) | Natural change (per 1000) | Crude migration change (per 1000) | TFR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1936 | 786,388 | ||||||||

| 1937 | 820,469 | ||||||||

| 1938 | 822,586 | 43.5 | |||||||

| 1939 | 857,951 | 44.6 | |||||||

| 1940 | 19,763,000 | 875,471 | 44.3 | ||||||

| 1941 | 20,208,000 | 878,935 | 43.5 | ||||||

| 1942 | 20,657,000 | 940,067 | 45.5 | ||||||

| 1943 | 21,165,000 | 963,317 | 45.5 | ||||||

| 1944 | 21,674,000 | 958,119 | 44.2 | ||||||

| 1945 | 22,233,000 | 999,093 | 44.9 | ||||||

| 1946 | 22,779,000 | 994,838 | 442,935 | 551,903 | 43.7 | 19.4 | 24.3 | ||

| 1947 | 23,440,000 | 1,079,816 | 390,087 | 689,729 | 46.1 | 16.6 | 29.5 | ||

| 1948 | 24,129,000 | 1,090,867 | 407,708 | 683,159 | 44.7 | 16.9 | 27.8 | ||

| 1949 | 24,833,000 | 1,109,446 | 438,970 | 670,476 | 46.0 | 17.7 | 28.3 | ||

| 1950 | 28,296,000 | 1,174,947 | 418,430 | 756,517 | 41.5 | 14.8 | 26.7 | ||

| 1951 | 29,110,000 | 1,183,788 | 458,238 | 725,550 | 40.7 | 15.7 | 24.9 | ||

| 1952 | 29,980,000 | 1,195,209 | 408,823 | 786,386 | 39.9 | 13.6 | 26.2 | ||

| 1953 | 30,904,000 | 1,261,775 | 446,127 | 815,648 | 40.8 | 14.4 | 26.4 | ||

| 1954 | 31,880,000 | 1,339,837 | 378,752 | 961,085 | 42.0 | 11.9 | 30.1 | ||

| 1955 | 32,906,000 | 1,377,917 | 407,522 | 970,395 | 41.9 | 12.4 | 29.5 | ||

| 1956 | 33,978,000 | 1,427,722 | 368,740 | 1,058,982 | 42.0 | 10.9 | 31.2 | ||

| 1957 | 35,095,000 | 1,485,202 | 414,545 | 1,070,657 | 42.3 | 11.8 | 30.5 | ||

| 1958 | 36,253,000 | 1,447,578 | 404,529 | 1,043,049 | 39.9 | 11.2 | 28.8 | ||

| 1959 | 37,448,000 | 1,589,606 | 396,924 | 1,192,682 | 42.4 | 10.6 | 31.8 | 0.1 | |

| 1960 | 38,677,000 | 1,608,174 | 402,545 | 1,205,629 | 41.6 | 10.4 | 31.2 | 0.6 | |

| 1961 | 39,939,000 | 1,647,006 | 388,857 | 1,258,149 | 41.2 | 9.7 | 31.5 | 0.1 | |

| 1962 | 41,234,000 | 1,705,481 | 403,046 | 1,302,435 | 41.4 | 9.8 | 31.6 | -0.2 | |

| 1963 | 42,564,000 | 1,756,624 | 412,834 | 1,343,790 | 41.3 | 9.7 | 31.6 | -0.3 | |

| 1964 | 43,931,000 | 1,849,408 | 408,275 | 1,441,133 | 42.1 | 9.3 | 32.8 | -1.7 | |

| 1965 | 45,339,000 | 1,888,171 | 404,163 | 1,484,008 | 41.6 | 8.9 | 32.7 | -1.7 | |

| 1966 | 46,784,000 | 1,954,340 | 424,141 | 1,530,199 | 41.8 | 9.1 | 32.7 | -1.9 | |

| 1967 | 48,264,000 | 1,981,363 | 420,298 | 1,561,065 | 41.1 | 8.7 | 32.3 | -1.7 | |

| 1968 | 49,788,000 | 2,058,251 | 452,910 | 1,605,341 | 41.3 | 9.1 | 32.2 | -1.7 | |

| 1969 | 51,361,000 | 2,037,561 | 458,886 | 1,578,675 | 39.7 | 8.9 | 30.7 | -0.1 | |

| 1970 | 52,988,000 | 2,132,630 | 485,656 | 1,646,974 | 40.2 | 9.2 | 31.1 | -0.4 | |

| 1971 | 54,669,000 | 2,231,399 | 458,323 | 1,773,076 | 40.8 | 8.4 | 32.4 | -1.7 | |

| 1972 | 56,396,000 | 2,346,002 | 476,206 | 1,869,796 | 41.6 | 8.4 | 33.2 | -2.6 | |

| 1973 | 58,156,000 | 2,572,287 | 458,915 | 2,113,372 | 44.2 | 7.9 | 36.3 | -6.3 | |

| 1974 | 59,931,000 | 2,522,580 | 433,104 | 2,089,476 | 42.1 | 7.2 | 34.9 | -5.4 | |

| 1975 | 61,708,000 | 2,254,497 | 435,888 | 1,818,609 | 36.5 | 7.1 | 29.5 | -0.7 | |

| 1976 | 63,486,000 | 2,366,305 | 455,660 | 1,910,645 | 37.3 | 7.2 | 30.1 | -2.1 | 5.7 |

| 1977 | 65,261,000 | 2,379,327 | 450,454 | 1,928,873 | 36.5 | 6.9 | 29.6 | -2.4 | |

| 1978 | 67,013,000 | 2,346,862 | 418,381 | 1,928,481 | 35.0 | 6.2 | 28.8 | -2.7 | |

| 1979 | 68,715,000 | 2,274,267 | 428,217 | 1,846,050 | 33.1 | 6.2 | 26.9 | -2.1 | |

| 1980 | 70,353,000 | 2,446,238 | 434,465 | 2,011,773 | 34.8 | 6.2 | 28.6 | -5.4 | |

| 1981 | 71,916,000 | 2,530,662 | 424,274 | 2,106,388 | 35.2 | 5.9 | 29.3 | -7.7 | 4.6 |

| 1982 | 73,416,000 | 2,392,849 | 412,345 | 1,980,504 | 32.6 | 5.6 | 27.0 | -6.7 | |

| 1983 | 74,880,000 | 2,609,088 | 413,403 | 2,195,685 | 34.8 | 5.5 | 29.3 | -10.0 | |

| 1984 | 76,351,000 | 2,511,894 | 410,550 | 2,101,344 | 32.9 | 5.4 | 27.5 | -8.4 | |

| 1985 | 77,859,000 | 2,655,671 | 414,003 | 2,241,668 | 34.1 | 5.3 | 28.8 | -9.6 | |

| 1986 | 79,410,000 | 2,577,045 | 400,079 | 2,176,966 | 32.5 | 5.0 | 27.4 | -8.0 | |

| 1987 | 80,999,000 | 2,794,390 | 400,280 | 2,394,110 | 34.5 | 4.9 | 29.6 | -10.0 | 3.8 |

| 1988 | 82,635,000 | 2,622,031 | 412,987 | 2,209,044 | 31.7 | 5.0 | 26.7 | -7.1 | |

| 1989 | 84,327,000 | 2,620,262 | 423,304 | 2,196,958 | 31.1 | 5.0 | 26.1 | -6.1 | |

| 1990 | 86,077,000 | 2,735,312 | 422,803 | 2,312,509 | 31.8 | 4.9 | 26.9 | -6.7 | 3.47 |

| 1991 | 87,890,000 | 2,756,447 | 411,131 | 2,345,316 | 31.4 | 4.7 | 26.7 | -6.1 | 3.37 |

| 1992 | 89,758,000 | 2,797,397 | 409,814 | 2,387,583 | 31.2 | 4.6 | 26.6 | -5.9 | 3.27 |

| 1993 | 91,654,000 | 2,839,686 | 416,335 | 2,423,351 | 31.0 | 4.5 | 26.4 | -5.9 | 3.18 |

| 1994 | 93,542,000 | 2,904,389 | 419,074 | 2,485,315 | 31.0 | 4.5 | 26.6 | -6.5 | 3.10 |

| 1995 | 95,393,000 | 2,750,444 | 430,278 | 2,320,166 | 28.8 | 4.5 | 24.3 | -5.0 | 3.02 |

| 1996 | 97,202,000 | 2,707,718 | 436,321 | 2,271,397 | 27.9 | 4.5 | 23.4 | -4.8 | 2.95 |

| 1997 | 98,969,000 | 2,698,425 | 440,437 | 2,257,988 | 27.3 | 4.5 | 22.8 | -5.1 | 2.88 |

| 1998 | 100,679,000 | 2,668,429 | 444,665 | 2,223,764 | 26.5 | 4.4 | 22.1 | -5.2 | 2.82 |

| 1999 | 102,317,000 | 2,769,089 | 443,950 | 2,325,139 | 27.1 | 4.3 | 22.7 | -6.8 | 2.77 |

| 2000 | 103,874,000 | 2,798,339 | 437,667 | 2,360,672 | 26.9 | 4.2 | 22.7 | -7.9 | 2.72 |

| 2001 | 105,340,000 | 2,767,610 | 443,127 | 2,324,483 | 26.3 | 4.2 | 22.1 | -8.3 | 2.67 |

| 2002 | 106,724,000 | 2,699,084 | 459,687 | 2,239,397 | 25.3 | 4.3 | 21.0 | -8.1 | 2.62 |

| 2003 | 108,056,000 | 2,655,894 | 472,140 | 2,183,754 | 24.6 | 4.4 | 20.2 | -8.0 | 2.58 |

| 2004 | 109,382,000 | 2,625,056 | 473,417 | 2,151,639 | 24.0 | 4.3 | 19.7 | -7.6 | 2.54 |

| 2005 | 110,732,000 | 2,567,906 | 495,240 | 2,072,666 | 23.2 | 4.5 | 18.7 | -6.6 | 2.50 |

| 2006 | 112,117,000 | 2,505,939 | 494,471 | 2,011,468 | 22.4 | 4.4 | 17.9 | -5.7 | 2.46 |

| 2007 | 113,530,000 | 2,655,083 | 514,420 | 2,140,663 | 23.4 | 4.5 | 18.9 | -6.5 | 2.42 |

| 2008 | 114,968,000 | 2,636,110 | 539,530 | 2,096,580 | 22.9 | 4.7 | 18.2 | -5.8 | 2.39 |

| 2009 | 116,423,000 | 2,577,214 | 564,673 | 2,012,541 | 22.1 | 4.9 | 17.3 | -4.8 | 2.36 |

| 2010 | 114,255,000 | 2,643,908 | 592,018 | 2,051,890 | 23.1 | 5.2 | 17.9 | -36.2 | 2.34 |

| 2011 | 115,683,000 | 2,586,287 | 590,693 | 1,995,594 | 22.3 | 5.1 | 17.2 | -5.5 | 2.32 |

| 2012 | 117,054,000 | 2,498,880 | 602,354 | 1,896,526 | 21.3 | 5.1 | 16.2 | -4.5 | 2.29 |

| 2013 | 118,395,000 | 2,478,889 | 623,599 | 1,855,290 | 20.9 | 5.3 | 15.6 | -4.4 | 2.27 |

| 2014 | 119,713,000 | 2,463,420 | 633,641 | 1,829,779 | 20.5 | 5.3 | 15.2 | -4.3 | 2.24 |

| 2015 | 121,005,000 | 2,353,596 | 655,694 | 1,697,902 | 19.4 | 5.4 | 14.0 | -3.4 | 2.22 |

| 2016 | 122,298,000 | 2,293,708 | 685,763 | 1,607,945 | 18.8 | 5.6 | 13.2 | -2.6 | 2.19 |

| 2017 | 123,415,000 | 2,234,039 | 703,047 | 1,530,992 | 18.1 | 5.8 | 12.3 | -3.4 | 2.17 |

| 2018 | 124,738,000 | 2,162,535 | 722,611 | 1,439,924 | 17.3 | 5.8 | 11.5 | -0.9 | 2.14 |

| 2019 | 125,930,000 | 2,092,214 | 747,784 | 1,344,430 | 16.5 | 5.9 | 10.6 | -1.2 | 2.09 |

| 2020 | 126,014,024 | 1,629,211 | 1,086,743 | 542,468 | 12.9 | 8.6 | 4.3 | -3.6 | 1.63(e) |

| 2021 | 126,705,138 | 1,912,178 | 1,122,249 | 789,929 | 15.1 | 8.8 | 6.3 | -0.8 | 1.91(e) |

| 2022 | 1,891,388 | 841,318 | 1,050,070 | 14.8 | 6.6 | 8.2 |

Current vital statistics

| Period | Live births | Deaths | Natural increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| January – September 2022 | 643,950 | ||

| January – September 2023 | 589,834 | ||

| Difference |

Estimates

The following estimates were prepared by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informatica:

| Crude birth rate (per 1000)[25] | Crude death rate (per 1000)[26] | Natural change (per 1000) | Total fertility rate[27] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | 5.7 | |||

| 1981 | 4.4 | |||

| 1987 | 3.8 | |||

| 1990 | 27.9 | 5.6 | 22.3 | 3.4 |

| 1991 | 27.5 | 5.5 | 22.0 | 3.3 |

| 1992 | 27.1 | 5.4 | 21.7 | 3.2 |

| 1993 | 26.8 | 5.3 | 21.5 | 3.1 |

| 1994 | 26.3 | 5.2 | 21.1 | 3.0 |

| 1995 | 25.9 | 5.2 | 20.7 | 3.0 |

| 1996 | 25.4 | 5.1 | 20.3 | 2.9 |

| 1997 | 24.8 | 5.1 | 19.7 | 2.8 |

| 1998 | 24.3 | 5.1 | 19.2 | 2.8 |

| 1999 | 23.9 | 5.1 | 18.8 | 2.7 |

| 2000 | 23.4 | 5.1 | 18.3 | 2.6 |

| 2001 | 23.0 | 5.1 | 17.9 | 2.6 |

| 2002 | 22.6 | 5.1 | 17.5 | 2.6 |

| 2003 | 22.2 | 5.2 | 17.0 | 2.5 |

| 2004 | 21.8 | 5.2 | 16.6 | 2.5 |

| 2005 | 21.5 | 5.2 | 16.3 | 2.5 |

| 2006 | 21.1 | 5.3 | 15.8 | 2.4 |

| 2007 | 20.8 | 5.3 | 15.5 | 2.4 |

| 2008 | 20.4 | 5.4 | 15.0 | 2.3 |

| 2009 | 20.1 | 5.5 | 14.6 | 2.3 |

| 2010 | 19.7 | 5.6 | 14.1 | 2.3 |

| 2011 | 19.4 | 5.6 | 13.8 | 2.3 |

| 2012 | 19.2 | 5.7 | 13.5 | 2.2 |

| 2013 | 19.0 | 5.7 | 13.3 | 2.2 |

| 2014 | 18.7 | 5.7 | 13.0 | 2.2 |

| 2015 | 18.5 | 5.7 | 12.8 | 2.2 |

| 2016 | 18.3 | 5.8 | 12.5 | 2.2 |

Life expectancy from 1893 to 1950

Life expectancy in Mexico from 1893 to 1950. Source: Our World In Data

| Years | 1893 | 1894 | 1895 | 1896 | 1897 | 1898 | 1899 | 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910[28] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy in Mexico | 23.3 | 26.6 | 29.5 | 28.8 | 26.2 | 27.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 26.7 | 28.4 | 28.7 | 29.1 | 26.8 | 27.8 | 28.0 | 28.7 | 29.2 | 28.0 |

| Years | 1920 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930[28] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy in Mexico | 34.0 | 32.6 | 33.5 | 32.8 | 32.1 | 34.2 | 40.3 | 34.5 | 35.4 | 34.0 |

| Years | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 | 1940[28] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy in Mexico | 37.7 | 38.4 | 37.3 | 38.2 | 40.4 | 38.3 | 36.8 | 39.4 | 45.5 | 39.0 |

| Years | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 | 1946 | 1947 | 1948 | 1949 | 1950[28] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy in Mexico | 42.6 | 39.8 | 42.8 | 43.2 | 44.2 | 44.8 | 46.3 | 48.3 | 45.8 | 50.7 |

UN estimates

The Population Department of the United Nations prepared the following estimates.[19]

| Period | Live births per year |

Deaths per year |

Natural change per year |

CBR* | CDR* | NC* | TFR* | IMR* | Life expectancy total |

Life expectancy males |

Life expectancy females |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950–1955 | 1 469 000 | 509 000 | 959 000 | 48.3 | 16.7 | 31.6 | 6.75 | 121 | 50.7 | 48.9 | 52.5 |

| 1955–1960 | 1 675 000 | 483 000 | 1 193 000 | 46.6 | 13.5 | 33.1 | 6.78 | 102 | 55.3 | 53.3 | 57.3 |

| 1960–1965 | 1 878 000 | 481 000 | 1 397 000 | 44.6 | 11.5 | 33.1 | 6.75 | 88 | 58.5 | 56.4 | 60.6 |

| 1965–1970 | 2 147 000 | 510 000 | 1 637 000 | 43.6 | 10.4 | 33.2 | 6.75 | 80 | 60.3 | 58.2 | 62.5 |

| 1970–1975 | 2 434 000 | 521 000 | 1 913 000 | 43.7 | 9.2 | 34.5 | 6.71 | 69 | 62.6 | 60.1 | 65.2 |

| 1975–1980 | 2 406 000 | 490 000 | 1 916 000 | 37.2 | 7.5 | 29.7 | 5.40 | 57 | 65.3 | 62.2 | 68.6 |

| 1980–1985 | 2 352 000 | 470 000 | 1 882 000 | 32.3 | 6.3 | 26.0 | 4.37 | 47 | 67.7 | 64.4 | 71.2 |

| 1985–1990 | 2 385 000 | 466 000 | 1 919 000 | 29.7 | 5.7 | 24.0 | 3.75 | 40 | 69.8 | 66.8 | 73.0 |

| 1990–1995 | 2 493 000 | 470 000 | 2 022 000 | 27.4 | 5.2 | 22.3 | 3.23 | 33 | 71.8 | 69.0 | 74.6 |

| 1995–2000 | 2 535 000 | 471 000 | 2 064 000 | 25.2 | 4.8 | 20.5 | 2.85 | 28 | 73.3 | 71.3 | 76.1 |

| 2000–2005 | 2 449 000 | 492 000 | 1 958 000 | 23.0 | 4.6 | 18.4 | 2.61 | 21 | 75.1 | 72.4 | 77.4 |

| 2005–2010 | 2 355 000 | 513 000 | 1 841 000 | 20.7 | 4.6 | 16.1 | 2.40 | 17 | 75.1 | 73.7 | 78.6 |

| 2010–2015 | 2 353 000 | 579 000 | 1 774 000 | 19.4 | 4.8 | 14.6 | 2.29 | 74.9 | |||

| 2015–2020 | 2 291 000 | 635 000 | 1 656 000 | 17.6 | 4.9 | 12.7 | 2.14 | 74.9 | |||

| 2020–2025 | 2 206 000 | 699 000 | 1 507 000 | 16.0 | 5.1 | 11.0 | 2.00 | ||||

| 2025–2030 | 2 105 000 | 773 000 | 1 332 000 | 14.6 | 5.4 | 9.2 | 1.89 | ||||

| 2030–2035 | 2 014 000 | 860 000 | 1 154 000 | 13.4 | 5.7 | 7.7 | 1.81 | ||||

| 2035–2040 | 1 936 000 | 960 000 | 976 000 | 12.5 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 1.76 | ||||

| * CBR = crude birth rate (per 1000); CDR = crude death rate (per 1000); NC = natural change (per 1000); IMR = infant mortality rate per 1000 births; TFR = total fertility rate (number of children per woman) | |||||||||||

Immigration to Mexico

| Place | Foreign-born population in Mexico | 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 797,266 | |||

| 2 | 56,810 | |||

| 3 | 52,948 | |||

| 4 | 36,234 | |||

| 5 | 35,361 | |||

| 6 | 25,976 | |||

| 7 | 20,763 | |||

| 8 | 19,736 | |||

| 9 | 18,693 | |||

| 10 | 12,439 | |||

| 11 | 10,547 | |||

| 12 | 9,080 | |||

| 13 | 8,689 | |||

| 14 | 8,670 | |||

| 15 | 6,860 | |||

| 16 | 6,619 | |||

| 17 | 6,532 | |||

| 18 | 5,895 | |||

| 19 | 5,731 | |||

| 20 | 5,539 | |||

| 21 | 5,339 | |||

| 22 | 4,030 | |||

| 23 | 3,995 | |||

| 24 | 3,803 | |||

| 25 | 2,849 | |||

| 26 | 2,813 | |||

| 27 | 2,706 | |||

| 28 | 2,656 | |||

| 29 | 2,505 | |||

| 30 | 2,321 | |||

| 31 | 1,916 | |||

| 32 | 1,439 | |||

| Other countries | 25,492 | |||

| TOTAL | 1,212,252 | |||

| Source: INEGI (2020)[29] | ||||

Aside from the original Spanish colonists, many Europeans immigrated to Mexico in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Non-Spanish immigrant groups included British, Irish, Italian, German, French and Dutch.[30] Large numbers of Middle Eastern immigrants arrived in Mexico during the same period, mostly from Syria and Lebanon.[31] Asian immigrants, mostly Chinese, some via the United States, settled in northern Mexico, whereas Koreans settled in central Mexico.[32]

During the 1970s and 1980s Mexico opened its doors to immigrants from Latin America, mainly political refugees from Argentina, Chile, Cuba, Peru, Colombia and Central America. The PRI governments, in power for most of the 20th century, had a policy of granting asylum to fellow Latin Americans fleeing political persecution in their home countries. A second wave of immigrants has come to Mexico as a result of the economic crises experienced by some countries in the region. The Argentine community is quite significant estimated to be somewhere between 11,000 and 30,000.[33][34]

Due to the 2008 Financial Crisis and the resulting economic decline and high unemployment in Spain, many Spaniards have been emigrating to Mexico to seek new opportunities.[35] For example, during the last quarter of 2012, a number of 7,630 work permits were granted to Spaniards.[36]

Mexico is also the country where the largest number of American citizens live abroad, with Mexico City playing host to the largest number of American citizens abroad in the world. The American Citizens Abroad Association estimated in 1999 that a little more than one million Americans live in Mexico (which represent 1% of the population in Mexico and 25% of all American citizens living abroad).[37] This immigration phenomenon could well be explained by the interaction of both countries under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), but also by the fact that Mexico has become a popular destination for retirees, especially the small towns: just in the State of Guanajuato, in San Miguel de Allende and its surroundings, 10,000 Americans have their residence.[38]

Discrepancies between the figures of official legal aliens and all foreign-born residents is quite large. The official figure for foreign-born residents in Mexico in 2000 was 493,000,[39] with a majority (86.9%) of these born in the United States (except Chiapas, where the majority of immigrants are from Central America). The six states with the most immigrants are Baja California (12.1% of total immigrants), Mexico City (11.4%), Jalisco (9.9%), Chihuahua (9%) and Tamaulipas (7.3%).[39]

Emigration from Mexico

The national net migration rate of Mexico is negative, estimated at -1.8 migrants per 1,000 population as of 2017[update].[41] The great majority of Mexican emigrants have moved to the United States of America. This migration phenomenon is not new, but it has been a defining feature in the relationship of both countries for most of the 20th century.[42] During World Wars I and II, the United States government approved the recruitment of Mexican workers in their territory, and tolerated unauthorized migration to obtain additional farm- and industrial-workers to fill the necessary spots vacated by the population in war, and to supply the increase in the demand for labor. Nonetheless, the United States unilaterally ended the wartime programs – in part as a result of arguments from labor and from civil-rights groups.[43]

In spite of that, emigration of Mexicans continued throughout the rest of the 20th century at varying rates. It grew significantly during the 1990s and continued to do so in the first years of the 2000s. In fact, it has been estimated that 37% of all Mexican immigrants to the United States in the 20th century arrived during the 1990s.[42] In 2000 approximately 20 million American residents identified themselves as either Mexican, Mexican-Americans or of Mexican origin, making "Mexican" the sixth-most cited ancestry of all US residents.[44]

In 2000 the INEGI estimated that about eight million Mexican-born people, which then was equivalent to 8.7% of the population of Mexico itself, lived in the United States of America.[45] In that year, the Mexican states sending the greatest numbers of emigrants to the United States were Jalisco (170,793), Michoacán (165,502), and Guanajuato (163,338); the total number of Mexican emigrants to the United States in 2000, both legal and illegal, was estimated at 1,569,157; the great majority of these were men.[46] Approximately 30% of emigrants come from rural communities.[47] In 2000, 260,650 emigrants returned to Mexico.[48] According to the Pew Hispanic Center in 2006, an estimated ten percent of all Mexican citizens lived in the United States.[49] The population of Mexican immigrants residing illegally in the United States fell from around seven million in 2007 to about 6.1 million in 2011.[50] This trajectory has been linked to the economic downturn which started in 2008 and which reduced available jobs, and to the introduction of stricter immigration laws in many States.[51][52][53][54] According to the Pew Hispanic Center the total number of Mexican-born people had stagnated in 2010 and then began to fall.[55]

After the Mexican-American community, Mexican Canadians are the second-largest group of emigrant Mexicans, with a population of over 50,000.[56] A significant but unknown number of mestizos of Mexican descent migrated to the Philippines during the era of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, when the Philippines was a territory under the rule of Mexico city.[57] Mexicans live throughout Latin America as well as in Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Arab Emirates.

| Emigration list from Mexico[58] Mexican residents in the world by countries | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Population | Position | Continent |

| 36,300,000[59] | 1 | North America | |

| 90,585[60] | 2 | North America | |

| 56,757[61] | 3 | Europe | |

| 14,481[62] | 4 | North America | |

| 13,377[63] | 5 | South America | |

| 8,848[64] | 6 | Europe | |

| 6,750[65] | 7 | South America | |

| 5,125[66] | 8 | Europe | |

| 4,872[67] | 9 | Oceania | |

| 4,601[68] | 10 | Europe | |

| 4,252[69] | 11 | Asia | |

| 3,758[70] | 12 | Europe | |

| 3,485[70] | 13 | Europe | |

| 3,075[71] | 14 | South America | |

| 2,794[72] | 15 | Europe | |

| 2,349[73] | 16 | North America | |

| 2,327[74] | 17 | North America | |

| 2,299[75] | 18 | North America | |

| 2,286[76] | 19 | South America | |

| 1,874[77] | 20 | South America | |

| 1,778[78] | 21 | South America | |

| The list includes also temporary residents (1–3 years' stay) | |||

Settlements, cities and municipalities

| Most populated municipalities | |

|---|---|

| Municipality of Guadalajara | |

| Municipality | Pop. (2005) |

| Ecatepec de Morelos | 1,688,258 |

| Guadalajara | 1,600,940 |

| Puebla | 1,485,941 |

| Tijuana | 1,410,700 |

| León | 1,325,210 |

| Juárez | 1,313,338 |

In 2005 Mexico had 187,938 localidades (lit. "localities" or "settlements"), which are census-designated places, which could be defined as a small town, a large city, or simply as a single unit housing in a rural area whether situated remotely or close to an urban area. A city is defined to be a settlement with more than 2,500 inhabitants. In 2005 there were 2,640 cities with a population between 2,500 and 15,000 inhabitants, 427 with a population between 15,000 and 100,000 inhabitants, 112 with a population between 100,000 and one million, and 11 with a population of more than one million.[79] All cities are considered "urban areas" and represent 76.5% of total population. Settlements with less than 2,500 inhabitants are considered "rural communities" (in fact, more than 80,000 of those settlements have only one or two housing units). Rural population in Mexico is 22.2% of total population.[79]

Municipalities (municipios in Spanish) and boroughs (delegaciones in Spanish) are incorporated places in Mexico, that is, second or third-level political divisions with internal autonomy, legally prescribed limits, powers and functions. In terms of second-level political divisions there are 2,438 municipalities and Mexico and 16 semi-autonomous boroughs (all within the Federal District). A municipality can be constituted by one or more cities one of which is the cabecera municipal (municipal seat). Cities are usually contained within the limits of a single municipality, with a few exceptions in which small areas of one city may extend to other adjacent municipalities without incorporating the city which serves as the municipal seat of the adjacent municipality. Some municipalities or cities within municipalities are further divided into delegaciones or boroughs. However, unlike the boroughs of the Federal District, these are third-level administrative divisions; they have very limited autonomy and no elective representatives.

Municipalities in central Mexico are usually very small in area and thus coextensive with cities (as is the case of Guadalajara, Puebla and León), whereas municipalities in northern and southeastern Mexico are much larger and usually contain more than one city or town that may not necessarily conform a single urban agglomeration (as is the case of Tijuana).

Metropolitan areas

A metropolitan area in Mexico is defined to be the group of municipalities that heavily interact with each other, usually around a core city.[80] In 2004, a joint effort between CONAPO, INEGI and the Ministry of Social Development (SEDESOL) agreed to define metropolitan areas as either:[80]

- the group of two or more municipalities in which a city with a population of at least 50,000 is located whose urban area extends over the limit of the municipality that originally contained the core city incorporating either physically or under its area of direct influence other adjacent predominantly urban municipalities all of which have a high degree of social and economic integration or are relevant for urban politics and administration; or

- a single municipality in which a city of a population of at least one million is located and fully contained, (that is, it does not transcend the limits of a single municipality); or

- a city with a population of at least 250,000 which forms a conurbation with other cities in the United States of America.

In 2004 there were 55 metropolitan areas in Mexico, in which close to 53% of the country's population lives. The most populous metropolitan area in Mexico is the Metropolitan Area of the Valley of Mexico, or Greater Mexico City, which in 2005 had a population of 19.23 million, or 19% of the nation's population. The next four largest metropolitan areas in Mexico are Greater Guadalajara (4.1 million), Greater Monterrey (3.7 million), Greater Puebla (2.1 million) and Greater Toluca (1.6 million),[81] whose added population, along with Greater Mexico City, is equivalent to 30% of the nation's population. Greater Mexico City was the fastest growing metropolitan area in the country since the 1930s until the late 1980s. Since then, the country has slowly become economically and demographically less centralized. From 2000 to 2005 the average annual growth rate of Greater Mexico City was the lowest of the five largest metropolitan areas, whereas the fastest growing metropolitan area was Puebla (2.0%) followed by Monterrey (1.9%), Toluca (1.8%) and Guadalajara (1.8%).[81]

| Rank | Name | State | Pop. | Rank | Name | State | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Valley of Mexico Monterrey |

1 | Valley of Mexico | Mexico City, State of Mexico, Hidalgo | 21,804,515 | 11 | Aguascalientes | Aguascalientes | 1,225,432 | Guadalajara Puebla–Tlaxcala |

| 2 | Monterrey | Nuevo León | 5,341,171 | 12 | San Luis Potosí | San Luis Potosí | 1,221,526 | ||

| 3 | Guadalajara | Jalisco | 5,286,642 | 13 | Mérida | Yucatán | 1,201,000 | ||

| 4 | Puebla–Tlaxcala | Puebla, Tlaxcala | 3,199,530 | 14 | Mexicali | Baja California | 1,031,779 | ||

| 5 | Toluca | State of Mexico | 2,353,924 | 15 | Saltillo | Coahuila | 1,031,779 | ||

| 6 | Tijuana | Baja California | 2,157,853 | 16 | Cuernavaca | Morelos | 1,028,589 | ||

| 7 | León | Guanajuato | 1,924,771 | 17 | Culiacán | Sinaloa | 1,003,530 | ||

| 8 | Querétaro | Querétaro | 1,594,212 | 18 | Morelia | Michoacán | 988,704 | ||

| 9 | Juárez | Chihuahua | 1,512,450 | 19 | Chihuahua | Chihuahua | 988,065 | ||

| 10 | La Laguna | Coahuila, Durango | 1,434,283 | 20 | Veracruz | Veracruz | 939,046 | ||

Demographic statistics according to the 2022 World Population Review.[85]

- One birth every 15 seconds

- One death every 39 seconds

- One net migrant every 9 minutes

- Net gain of one person every 24 seconds

Demographic statistics according to the CIA World Factbook, unless otherwise indicated.[86]

Median age

- total: 29.3 years. Country comparison to the world: 132nd

- male: 28.2 years

- female: 30.4 years (2020 est.)

- total: 28.6 years Country comparison to the world: 135th

- male: 27.5 years

- female: 29.7 years (2018 est.)

Contraceptive prevalence rate

- 73.1% (2018)

- 66.9% (2015)

Mother's mean age at first birth

- 21.3 years (2008 est.)

Major infectious diseases

- degree of risk: intermediate (2020)

- food or waterborne diseases: bacterial diarrhea and hepatitis A

- vectorborne diseases: dengue fever

note: a new coronavirus is causing sustained community spread of respiratory illness (COVID-19) in Mexico; sustained community spread means that people have been infected with the virus, but how or where they became infected is not known, and the spread is ongoing; illness with this virus has ranged from mild to severe with fatalities reported; as of June 6, 2022, Mexico has reported a total of 5,782,405 cases of COVID-19 or 4,484.8 cumulative cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 population with a total of 324,966 cumulative deaths or a rate of 252 cumulative deaths per 100,000 population; as of May 20, 2022, 66.68% of the population has received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine

Dependency ratios

- total dependency ratio: 51.4 (2015 est.)

- youth dependency ratio: 41.6 (2015 est.)

- elderly dependency ratio: 9.8 (2015 est.)

- potential support ratio: 10.2 (2015 est.)

Urbanization

- urban population: 81.3% of total population (2022)

- rate of urbanization: 1.4% annual rate of change (2020–25 est.)

- urban population: 80.2% of total population (2018)

- rate of urbanization: 1.59% annual rate of change (2015–20 est.)

Obesity – adult prevalence rate

- 28.9% (2016) Country comparison to the world: 29th

Children under the age of 5 years underweight

- 4.7% (2018/19) Country comparison to the world: 80th

- 4.2% (2016) Country comparison to the world: 87th

Education expenditures

- 4.3% of GDP (2018) Country comparison to the world: 92nd

- 5.2% of GDP (2015) Country comparison to the world: 59th

Literacy

definition: age 15 and over can read and write (2016 est.)

- total population: 95.2%

- male: 96.1%

- female: 94.5% (2020)

School life expectancy (primary to tertiary education)

- total: 15 years

- male: 15 years

- female: 15 years (2019)

Unemployment, youth ages 15–24

- total: 8.1%

- male: 7.8%

- female: 8.7% (2020 est.)

Mexico is ethnically diverse. The second article of the Mexican Constitution defines the country to be a pluricultural state originally based on its indigenous peoples.

Regardless of ethnicity, the majority of Mexicans are united under the same national identity.[87] This is the product of an ideology strongly promoted by Mexican academics such as Manuel Gamio and José Vasconcelos known as mestizaje, whose goal was that of Mexico becoming a racially and culturally homogeneous country.[88][87][89] The ideology's influence was reflected in Mexico's national censuses of 1921 and 1930: in the former, which was Mexico's first-ever national census (but second-ever if the census made in colonial times is taken into account)[90] that considered race, approximately 60% of Mexico's population identified as Mestizos,[91] and in the latter, Mexico's government declared that all Mexicans were now Mestizos, for which racial classifications would be dropped in favor of language-based ones in future censuses.[92] During most of the 20th century these censuses' results were taken as fact, with extraofficial international publications often using them as a reference to estimate Mexico's racial composition,[93][94][95] but in recent time historians and academics have claimed that said results are not accurate, as in its efforts to homogenize Mexico, the government inflated the Mestizo label's percentage by classifying a good number of people as such regardless of whether they were of actual mixed ancestry or not,[96][97][98][99] pointing out that an alteration so drastic of population trends compared to earlier censuses such as New Spain's 1793 census (on which Europeans were estimated to be 18% to 22% of the population, Mestizos 21% to 25% and Indigenous peoples 51% to 61%)[90] is not possible and that the frequency of marriages between people of different ancestries in colonial and early independent Mexico was low.[100][101] It is also observed that when asked directly about their ethno-racial identification, many Mexicans nowadays do not identify as Mestizos,[102] would not agree to be labeled as such,[103] and that "static" ethnoracial labels such as "White" “Black” or "Indian" are far more prominent in contemporary Mexican society than the "Mestizo" one is, whose use is mostly limited to intellectual circles, a result of the label's constantly-changing and subjective definition.[104] Mexico is a diverse country both geographically and ethnically, according to CIA, the World Factbook, the ethnic composition of Mexico is 62% Mestizo, 21% Predominantly Amerindian (in which more than 50-60% of the DNA is indigenous), 7% Amerindian, and 10% other (mostly full-blooded European).[105] However estimates vary by methodology.

Mestizo

A large majority of Mexicans have been classified as "Mestizos", meaning in modern Mexican usage that they identify fully neither with any indigenous culture nor with a Spanish cultural heritage, but rather identify as having cultural traits incorporating elements from both indigenous and Spanish traditions. By the deliberate efforts of post-revolutionary governments, the "Mestizo identity" was constructed as the base of the modern Mexican national identity, through a process of cultural synthesis referred to as mestizaje [mestiˈsaxe]. Mexican politicians and reformers such as José Vasconcelos and Manuel Gamio were instrumental in building a Mexican national identity upon this concept.[106][107]

Since the Mestizo identity promoted by the government is more of a cultural identity than a biological one it has achieved a strong influence in the country, a good number of phenotypically white people identifying with it, leading to being considered Mestizos in Mexico's demographic investigations and censuses due to the ethnic criteria having its base on cultural traits rather than biological ones.[108] A similar situation occurs regarding the distinctions between Indigenous peoples and Mestizos: while the term Mestizo is sometimes used in English with the meaning of a person with mixed indigenous and European blood, In Mexican society an indigenous person can be considered mestizo.[109] and a person with none or a very low percentage of indigenous genetic heritage would be considered fully indigenous either by speaking an indigenous language or by identifying with a particular indigenous cultural heritage.[110][111][112] In the Yucatán peninsula the word Mestizo has a different meaning, with it being to refer to the Maya-speaking populations living in traditional communities, because during the caste war of the late 19th century those Maya who did not join the rebellion were classified as Mestizos.[99] In Chiapas the word "Ladino" is used instead of mestizo.[113]

Given that the word Mestizo has different meanings in Mexico, estimates of the Mexican Mestizo population vary widely. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, which uses a biology-based approach, between one half and two-thirds of the Mexican population is Mestizo[114] whereas a culture-based criteria estimates a percentage as high as 90%.[92] Recent research based on self-identification nonetheless, has observed that many Mexicans do not identify as mestizos[102] and would not agree to be labeled as such,[103] with "static" racial labels such as White, Indian, Black etc. being more commonly used.[104]

The use of variated methods and criteria to quantify the number of Mestizos in Mexico is not new: Since several decades ago, many authors have analyzed colonial censuses data and have made different conjectures respecting the ethnic composition of the population of colonial Mexico/New Spain. There are Historians such as Gonzalo Aguirre-Beltrán who claimed in 1972 that practically the totality of New Spain's population, in reality, were Mestizos, using to back up his claims arguments such as that affairs of Spaniards with non-Europeans due to the alleged absence of female European immigrants were widespread as well as there being a huge desire of Mestizos to "pass" as Spaniards, this because Spanishness was seen as a symbol of high status.[115][116] Other historians however, point that Aguirre-Beltran numbers tend to have inconsistencies and take too much liberties (it is pointed out in the book Ensayos sobre historia de la población. México y el Caribe 2 published in 1998 that on 1646, when according to historic registers the mestizo population was of 1% he estimates it to be 16.6% already, with this being attributed to him interpreting the data in a way convenient for a historic narrative),[117][97] often omitting data of New Spain's northern and western provinces.[118] His self-made classifications thus, although could be plausible, are not useful for precise statistical analysis.[119] According 21st-century historians, Aguirre Beltran also disregards facts such as the population dynamics of New Spain being different depending on the region at hand (i.e. miscegenation couldn't happen in a significant amount in regions on which the native population was openly hostile until early 20th century, such as most of New Spain's internal provinces, which nowadays are the northern and western regions of Mexico),[97] or that historic accounts made by investigators at the time consistently observed that New Spain's European population was notoriously concerned with preserving their European heritage, with practices such as inviting relatives and friends directly from Spain or favoring Europeans for marriage even if they were from a lower socioeconomic level than them being common.[120][117][97] Newer publications that do cite Aguirre-Beltran's work take those factors into consideration, stating that the Spaniard/Euromestizo/Criollo ethnic label was composed on its majority by descendants of Europeans albeit the category may have included people with some non-European ancestry.[121]

Indigenous peoples

Prior to contact with Europeans the indigenous people of Mexico had not had any kind of shared identity.[122] Indigenous identity was constructed by the dominant Euro-Mestizo majority and imposed upon the indigenous people as a negatively defined identity, characterized by the lack of assimilation into modern Mexico. Indigenous identity therefore became socially stigmatizing.[123] Cultural policies in early post-revolutionary Mexico were paternalistic towards the indigenous people, with efforts designed to help indigenous peoples achieve the same level of progress as the rest of society, eventually assimilating indigenous peoples completely to Mestizo Mexican culture, working toward the goal of eventually solving the "Indian problem" by transforming indigenous communities into mestizo communities.[124]

The category of "indígena" (indigenous) in Mexico has been defined based on different criteria throughout history. This means that the percentage of the Mexican population defined as "indigenous" varies according to the definition applied. It can be defined narrowly according to a linguistic criterion, including only persons that speak an Indigenous language. Based on this criterion, approximately 6.1% of the population is Indigenous.[125][126] Nonetheless, activists for the rights of indigenous peoples have referred to the usage of this criterion for census purposes as "statistical genocide."[127][128]

Other surveys made by the Mexican government do count as Indigenous all persons who speak an indigenous language and people who do not speak indigenous languages nor live in indigenous communities but self-identify as Indigenous.

According to these criteria, the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas, or CDI in Spanish) and the INEGI (Mexico's National Institute of Statistics and Geography), state that there are 15.7 million indigenous people in Mexico of many different ethnic groups,[129] which constitute 14.9% of the population in the country.[130]

Finally, according to the latest intercensal survey carried out by the Mexican government in 2015, Indigenous people make up 21.5% of Mexico's population. In this occasion, people who self-identified as "Indigenous" and people who self-identified as "partially Indigenous" were classified in the "Indigenous" category altogether.[131] Indigenous people number 11.8 million people, or 9.36% of the Mexican population, in the 2020 census. Here, indigenous peoples are counted based on affiliation with an ethnic group.[132]

| Largest indigenous peoples | |

|---|---|

| Mayas in Chiapas | |

| Group | Number |

| Nahua peoples (Nawatlaka) | 2,445,969 |

| Maya (Maaya) | 1,475,575 |

| Zapotec (Binizaa) | 777,253 |

| Mixtec (Ñuu sávi) | 726,601 |

| Otomí (Hñähñü) | 646,875 |

| Totonac (Tachihuiin) | 411,266 |

| Source: CDI (2000) Archived September 15, 2019, at the Wayback Machine | |

The Mexican constitution not only recognizes the 62 indigenous peoples living in Mexican territory but also grants them autonomy and protects their culture and languages. This protection and autonomy is extended to those Amerindian ethnic groups which have migrated from the United States – like the Cherokees and Kickapoos — and Guatemala during the 19th and 20th centuries. Municipalities in which indigenous peoples are located can keep their normative traditional systems in relation to the election of their municipal authorities. This system is known as Usos y Costumbres, roughly translated as "customs and traditions".

According to official statistics —as reported by the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples or CDI— Amerindians make up 10–14%[133] of the country's population, more than half of them (5.4% of total population) speak an indigenous language and a tenth (1.2% of total population) do not speak Spanish.[134] Official statistics of the CDI[135] report that the states with the greatest percentage of people who speak an Amerindian language or identify as Amerindian are Yucatán (59%), Oaxaca (48%), Quintana Roo (39%), Chiapas (28%), Campeche (27%), Hidalgo (24%), Puebla (19%), Guerrero (17%), San Luis Potosí (15%) and Veracruz (15%). Oaxaca is the state with the greatest number of distinct indigenous peoples and languages in the country.

White Mexicans

White Mexicans are Mexican citizens of full or majority European descent.[136] This ethnic group contrasts with the Afro-Mexican and Indigenous Mexican groups in the fact that phenotype (hair color, skin color etc.) is often used as the main criterion to delineate it.[137][138][136] Spaniards and other Europeans began arriving in Mexico during the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire and continued immigrating to the country during colonial and independent Mexico. According to 20th- and 21st-century academics, large scale intermixing between the European immigrants and the native Indigenous peoples would produce a Mestizo group which would become the overwhelming majority of Mexico's population by the time of the Mexican revolution.[139] However, according to church registers from the colonial times, the majority (73%) of Spanish men married with Spanish women. Said registers also put in question other narratives held by contemporary academics, such as European immigrants who arrived to Mexico being almost exclusively men or that "pure Spanish" people were all part of a small powerful elite as Spaniards were often the most numerous ethnic group in the colonial cities[140][141] as there were menial workers and people in poverty who were of complete Spanish origin.[142]

Estimates of Mexico's white population differ greatly in both, methodology and percentages given, extra-official sources such as The World Factbook and Encyclopedia Britannica, which use the 1921 census results as the base of their estimations, calculate Mexico's White population as only 9%[143] or between one tenth to one fifth[144] (the results of the 1921 census, however, have been contested by various historians and deemed inaccurate).[101] Surveys that account for phenotypical traits and have performed actual field research suggest rather higher percentages: using the presence of blond hair as reference to classify a Mexican as white, the Metropolitan Autonomous University of Mexico calculated the percentage of said ethnic group at 23%.[145] With a similar methodology, the American Sociological Association obtained a percentage of 18.8% having its higher frequency on the North region (22.3%–23.9%) followed by the Center region (18.4%–21.3%) and the South region (11.9%).[146]

Another study made by the University College London in collaboration with Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History found that the frequencies of blond hair and light eyes in Mexicans are of 18% and 28% respectively,[84] surveys that use as reference skin color such as those made by Mexico's National Council to Prevent Discrimination and Mexico's National Institute of Statistics and Geography reported a percentages of 47% in 2010[147][148][149] and 49% in 2017[150][151] respectively. A study performed in hospitals of Mexico City suggests that socioeconomic factors influence the frequency of Mongolian spots among newborns, as evidenced by the higher prevalence of 85% in newborns from a public institution, typically associated with lower socioeconomic status, compared to a 33% prevalence in newborns from private hospitals, which generally cater to families with higher socioeconomic status.[152] The Mongolian spot appears with a very high frequency (85–95%) in Asian, Native American, and African children.[153] The skin lesion reportedly almost always appears on South American[154] and Mexican children who are racially Mestizos,[155] while having a very low frequency (5–10%) in Caucasian children.[156] According to the Mexican Social Security Institute (shortened as IMSS) nationwide, around half of Mexican babies have the Mongolian spot.[157]

Mexico's northern and western regions have the highest percentages of European population, with the majority of the people not having native admixture or being of predominantly European ancestry, resembling in aspect that of northern Spaniards.[158] In the north and west of Mexico, the indigenous populations were substantially smaller than those found in central and southern Mexico, and also much less organized, thus they remained isolated from the rest of the population or even in some cases were hostile towards Mexican colonists. The northeast region, in which the indigenous population was eliminated by early European settlers, became the region with the highest proportion of whites during the Spanish colonial period. However, recent immigrants from southern Mexico have been changing, to some degree, its demographic trends.[citation needed]

While the majority of European immigration to Mexico has been Spanish with the first wave starting with the colonization of America and the last one being a consequence of the Spanish Civil War of 1937,[159] immigrants from other European countries have arrived to Mexico as well: during the Second Mexican Empire the immigration was mostly French, and during the late 19th and early 20th centuries spurred by government policies of Porfirio Díaz, migrants mainly from Italy, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Germany followed taking advantage of the liberal policies then valid in Mexico and went into merchant, industrial and educational ventures while others arrived with no or limited capital, as employees or farmers.[160] Most settled in Mexico City, Veracruz, Yucatán, and Puebla. Significant numbers of German immigrants also arrived during and after the First and Second World Wars.[30][161] Additionally small numbers of White Americans, Croats, Greeks, Poles, Romanians, Russians and Ashkenazi Jews came.[161] The European Jewish immigrants joined the Sephardic community that lived in Mexico since colonial times, though many lived as Crypto-Jews, mostly in the northern states of Nuevo León and Tamaulipas.[162] Some communities of European immigrants have remained isolated from the rest of the general population since their arrival, among them the German-speaking Mennonites from Russia of Chihuahua and Durango,[163] and the Venetos of Chipilo, Puebla, which have retained their original languages.[164]

However, ethnicity in Mexico is not as clear cut as it is in the English speaking world, and "mestizos" are somewhat prone to identifying as "white" if asked. According to Pew Research, 60% of Mexicans identify as white when asked about their race.[165]

Afro-Mexicans

Afro-Mexicans are an ethnic group that predominate in certain areas of Mexico, such as the Costa Chica of Oaxaca and the Costa Chica of Guerrero, Veracruz (e.g. Yanga) and in some towns in northern Mexico. The existence of black people in Mexico is often unknown, denied or diminished both in Mexico and abroad for different reasons: their small numbers, continuous intermarriage and assimilation with non-African populations over various generations, as was often the case in Spanish territories and Mexico's tradition of defining itself as a "mestizaje" or mixing of European and indigenous. Mexico did have an active slave trade during the colonial period, but it wasn't as prominent as the one seen elsewhere in the Americas, which led to the number of free black people eventually surpassing that of enslaved ones. The institution was already in decay by the late 1700s and by the 19th century slavery and ethnic categorization at birth (see casta) have been abolished with the Mexican independence. After this the creation of a national Mexican identity, especially after the Mexican Revolution, emphasized Mexico's indigenous and European past, actively or passively eliminating its African one from popular consciousness.

The majority of Mexico's native Afro-descendants are Afromestizos. Individuals with significantly high amounts of African ancestry make up a very low percentage of the total Mexican population, the majority being recent black immigrants from Africa, the Caribbean and elsewhere in the Americas. According to the Intercensal survey carried out by the Mexican government, Afro-Mexicans make up 2.4% of Mexico's population,[125] the Afro-Mexican category in the Intercensal survey includes people who self-identified solely as African and people who self-identified as partially African. The survey also states that 64.9% (896,829) of Afro-Mexicans also identified as indigenous, with 9.3% being speakers of indigenous languages.[131]

A number of black Mexicans descend from recent immigrants from Haiti, Africa, and rest of the Caribbean.

Arab Mexicans

An Arab Mexican is a Mexican citizen of Arabic-speaking origin who can be of various ancestral origins. The vast majority of Mexico's 1.1 million Arabs are from either Lebanese, Syrian, Iraqi, or Palestinian background.[31]

The interethnic marriage in the Arab community, regardless of religious affiliation, is very high; most community members have only one parent who has Arab ethnicity. As a result of this, the Arab community in Mexico shows marked language shift away from Arabic. Only a few speak any Arabic, and such knowledge is often limited to a few basic words. Instead the majority, especially those of younger generations, speak Spanish as a first language. Today, the most common Arabic surnames in Mexico include Nader, Hayek, Ali, Haddad, Nasser, Malik, Abed, Mansoor, Harb and Elias.

Arab immigration to Mexico started in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[167] Roughly 100,000 Arabic-speakers settled in Mexico during this time period. They came mostly from Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, and Iraq and settled in significant numbers in Nayarit, Puebla, Mexico City and the northern part of the country (mainly in the states of Baja California, Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, Sinaloa, Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Durango, as well as the city of Tampico and Guadalajara. The term "Arab Mexican" may include ethnic groups that do not in fact identify as Arab.

During the Israel-Lebanon war in 1948 and during the Six-Day War, thousands of Lebanese left Lebanon and went to Mexico. They first arrived in Veracruz. Although Arabs made up less than 5% of the total immigrant population in Mexico during the 1930s, they constituted half of the immigrant economic activity.[31]

Immigration of Arabs in Mexico has influenced Mexican culture, in particular food, where they have introduced Kibbeh, Tabbouleh and even created recipes such as Tacos Árabes. By 1765, Dates, which originated from the Middle East, were introduced into Mexico by the Spaniards.[168] The fusion between Arab and Mexican food has highly influenced the Yucatecan cuisine.[169]

Another concentration of Arab-Mexicans is in Baja California facing the U.S.-Mexican border, esp. in cities of Mexicali in the Imperial Valley U.S./Mexico, and Tijuana across from San Diego with a large Arab American community (about 280,000), some of whose families have relatives in Mexico. 45% of Arab Mexicans are of Lebanese descent.

The majority of Arab-Mexicans are Christians who belong to the Maronite Church, Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Rite Catholic Churches.[170] A scant number are Muslims.

Asian Mexicans

Although Asian Mexicans make up less than 1% of the total population of modern Mexico, they are nonetheless a notable minority. Due to the historical and contemporary perception in Mexican society of what constitutes Asian culture (associated with the Far East rather than the Near East), Asian Mexicans typically refers to those of East Asian descent, and may also include those of South and Southeast Asian descent. For Mexicans of West Asian descent, see the Middle Eastern Mexicans section.

Asian immigration began with the arrival of Filipinos to Mexico during the Spanish period. For two and a half centuries, between 1565 and 1815, many Filipinos and Mexicans sailed to and from Mexico and the Philippines as sailors, crews, slaves, prisoners, adventurers and soldiers in the Manila-Acapulco Galleon assisting Spain in its trade between Asia and the Americas. Also on these voyages, thousands of Asian individuals (mostly males) were brought to Mexico as slaves and were called "Chino",[171] which means Chinese, although in reality they were of diverse origins, including Koreans, Japanese, Malays, Filipinos, Javanese, Cambodians, Timorese, and people from Bengal, India, Ceylon, Makassar, Tidore, Terenate, and China.[172][173][174] A notable example is the story of Catarina de San Juan (Mirra), an Indian girl captured by the Portuguese and sold into slavery in Manila. She arrived in New Spain and eventually she gave rise to the "China Poblana".

These early individuals are not very apparent in modern Mexico for two main reasons: the widespread mestizaje of Mexico during the Spanish period and the common practice of Chino slaves to "pass" as Indios (the indigenous people of Mexico) to attain freedom. As had occurred with a large portion of Mexico's black population, over generations the Asian populace was absorbed into the general Mestizo population. Facilitating this miscegenation was the assimilation of Asians into the indigenous population. The indigenous people were legally protected from chattel slavery, and by being recognized as part of this group, Asian slaves could claim they were wrongly enslaved.

Asians, predominantly Chinese, became Mexico's fastest-growing immigrant group from the 1880s to the 1920s, exploding from about 1,500 in 1895 to more than 20,000 in 1910.[175]

Romani Mexicans

Romani people have settled in Mexico since the colonial era.[176] There are around 50,000 Vlax Romani in Mexico.[177]

Official censuses

Historically, population studies and censuses have never been up to the standards that a population as diverse and numerous such as Mexico's require: the first racial census was made in 1793, being also Mexico's (then known as New Spain) first ever nationwide population census. Since only part of its original datasets survive, most of what is known of it comes from essays made by researchers who back in the day used the census' findings as reference for their own works. More than a century would pass until the Mexican government conducted a new racial census in 1921 (some sources assert that the census of 1895 included a comprehensive racial classification;[139] however, according to the historic archives of Mexico's National Institute of Statistics, that was not the case).[178] While the 1921 census was the last time the Mexican government conducted a census that included a comprehensive racial classification, in recent years it has conducted nationwide surveys to quantify most of the ethnic groups who inhabit the country as well as the social dynamics and inequalities between them.

1793 census

Also known as the "Revillagigedo census" from the name of the Count who ordered that it be conducted, this census was the first nationwide population census of Mexico (then known as the Viceroyalty of New Spain). Most of its original datasets have reportedly been lost, so most of what is known about it nowadays comes from essays and field investigations made by academics who had access to the census data and used it as reference for their works, such as Prussian geographer Alexander von Humboldt. Each author gives different estimations for each racial group in the country although they don't vary greatly, with Europeans ranging from 18% to 22% of New Spain's population, Mestizos from 21% to 25%, Indians from 51% to 61%, and Africans from 6,000 and 10,000. The estimations given for the total population range from 3,799,561 to 6,122,354. It is concluded then, that across nearly three centuries of colonization, the population growth trends of whites and mestizos were even, while the total percentage of the indigenous population decreased at a rate of 13%–17% per century. The authors assert that rather than whites and mestizos having higher birthrates, the reason for the indigenous population's numbers decreasing lies in their suffering higher mortality rates due to living in remote locations rather than in cities and towns founded by the Spanish colonists or in being at war with them. For the same reasons, the number of Indigenous Mexicans presents the greatest variation range between publications, as in some cases their numbers in a given location were estimated rather than counted, leading to possible overestimations in some provinces and possible underestimations in others.[179]

| Intendecy or territory | European population (%) | Indigenous population (%) | Mestizo population (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| México (only the State of Mexico and Mexico City) | 16.9% | 66.1% | 16.7% |

| Puebla | 10.1% | 74.3% | 15.3% |

| Oaxaca | 06.3% | 88.2% | 05.2% |

| Guanajuato | 25.8% | 44.0% | 29.9% |

| San Luis Potosí | 13.0% | 51.2% | 35.7% |

| Zacatecas | 15.8% | 29.0% | 55.1% |

| Durango | 20.2% | 36.0% | 43.5% |

| Sonora | 28.5% | 44.9% | 26.4% |

| Yucatán | 14.8% | 72.6% | 12.3% |

| Guadalajara | 31.7% | 33.3% | 34.7% |

| Veracruz | 10.4% | 74.0% | 15.2% |

| Valladolid | 27.6% | 42.5% | 29.6% |

| Nuevo México | ~ | 30.8% | 69.0% |

| Vieja California | ~ | 51.7% | 47.9% |

| Nueva California | ~ | 89.9% | 09.8% |

| Coahuila | 30.9% | 28.9% | 40.0% |

| Nuevo León | 62.6% | 05.5% | 31.6% |

| Nuevo Santander | 25.8% | 23.3% | 50.8% |

| Texas | 39.7% | 27.3% | 32.4% |

| Tlaxcala | 13.6% | 72.4% | 13.8% |

~Europeans are included within the Mestizo category.

Regardless of the possible inaccuracies related to the counting of Indigenous peoples living outside of the colonized areas, the effort that New Spain's authorities put into considering them as subjects is worth mentioning, as censuses made by other colonial or post-colonial countries did not consider American Indians to be citizens or subjects; for example, the censuses made by the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata would only count the inhabitants of the colonized settlements.[180] Another example is the censuses made by the United States, which did not include Indigenous peoples living among the general population until 1860, and indigenous peoples as a whole until 1900.[181]

1921 census

Made right after the consummation of the Mexican revolution, the social context in which this census was conducted makes it particularly unique, as the government of the time was in the process of rebuilding the country and was looking to unite all Mexicans in a single national identity. The 1921 census' final results in regards to race, which assert that 59.3% of the Mexican population self-identified as Mestizo, 29.1% as Indigenous, and only 9.8% as White, were then essential in cementing the mestizaje ideology (which asserts that the Mexican population as a whole is product of the admixture of all races), which shaped Mexican identity and culture through the 20th century and remains prominent nowadays, with extraofficial international publications such as The World Factbook and Encyclopædia Britannica using the 1921 census as a reference to estimate Mexico's racial composition up to this day.[93][114]

Nonetheless, in recent times, the census' results have been subjected to scrutiny by historians, academics and social activists alike, who assert that such drastic alterations on demographic trends with respect to the 1793 census are impossible and cite, among other statistics, the relatively low frequency of marriages between people of different continental ancestries in colonial and early independent Mexico.[182] It is claimed that the mestizaje process sponsored by the state was more "cultural than biological", which resulted in the numbers of the Mestizo Mexican group being inflated at the expense of the identity of other races.[183] Controversies aside, this census constituted the last time the Mexican Government conducted a comprehensive racial census with the breakdown by states being the following (foreigners and people who answered "other" not included):[184]

| Federative Units | Mestizo Population (%) | Amerindian Population (%) | White Population (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aguascalientes | 66.12% | 16.70% | 16.77% |

| Baja California (Distrito Norte) |

72.50% | 07.72% | 00.35% |

| Baja California (Distrito Sur) |

59.61% | 06.06% | 33.40% |

| Campeche | 41.45% | 43.41% | 14.17% |

| Coahuila | 77.88% | 11.38% | 10.13% |

| Colima | 68.54% | 26.00% | 04.50% |

| Chiapas | 36.27% | 47.64% | 11.82% |

| Chihuahua | 50.09% | 12.76% | 36.33% |

| Durango | 89.85% | 09.99% | 00.01% |

| Guanajuato | 96.33% | 02.96% | 00.54% |

| Guerrero | 54.05% | 43.84% | 02.07% |

| Hidalgo | 51.47% | 39.49% | 08.83% |

| Jalisco | 75.83% | 16.76% | 07.31% |

| Mexico City | 54.78% | 18.75% | 22.79% |

| State of Mexico | 47.71% | 42.13% | 10.02% |

| Michoacán | 70.95% | 21.04% | 06.94% |

| Morelos | 61.24% | 34.93% | 03.59% |

| Nayarit | 73.45% | 20.38% | 05.83% |

| Nuevo León | 75.47% | 05.14% | 19.23% |

| Oaxaca | 28.15% | 69.17% | 01.43% |

| Puebla | 39.34% | 54.73% | 05.66% |

| Querétaro | 80.15% | 19.40% | 00.30% |

| Quintana Roo | 42.35% | 20.59% | 15.16% |

| San Luis Potosí | 61.88% | 30.60% | 05.41% |

| Sinaloa | 98.30% | 00.93% | 00.19% |

| Sonora | 41.04% | 14.00% | 42.54% |

| Tabasco | 53.67% | 18.50% | 27.56% |

| Tamaulipas | 69.77% | 13.89% | 13.62% |

| Tlaxcala | 42.44% | 54.70% | 02.53% |

| Veracruz | 50.09% | 36.60% | 10.28% |

| Yucatán | 33.83% | 43.31% | 21.85% |

| Zacatecas | 86.10% | 08.54% | 05.26% |

When the 1921 census' results are compared with the results of Mexico's recent censuses[131] as well as with modern genetic research,[185] there is high consistency with respect to the distribution of Indigenous Mexicans across the country, with states located in south and south-eastern Mexico having both the highest percentages of population who self-identify as Indigenous and the highest percentages of Amerindian genetic ancestry. However, this is not the case when it comes to European Mexicans, as there are instances in which states that have been shown through scientific research to have a considerably high European ancestry are reported to have very small white populations in the 1921 census, with the most extreme case being that of the state of Durango, where the aforementioned census asserts that only 0.01% of the state's population (33 persons) self-identified as "white" while modern scientific research shows that the population of Durango has similar genetic frequencies to those found on European peoples (with the state's Indigenous population showing almost no foreign admixture either).[186] Various authors theorize that the reason for these inconsistencies may lie in the Mestizo identity promoted by the Mexican government, which reportedly led to people who are not biologically Mestizos to identify themselves as such.[108][187]

The present day

The following table is a compilation of, when possible, official nationwide surveys conducted by the Mexican government which have attempted to quantify different Mexican ethnic groups. Given that, for the most part, each ethnic group was estimated by different surveys with different methodologies and years apart rather than on a single comprehensive racial census, some groups could overlap with others and be overestimated or underestimated.

| Race or ethnicity | Population (est.) | Percentage (est.) | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous | 11,800,000 | 9.36% | 2020[188] |

| Black | 2,576,213 | 2.4% | 2020[189] |

| Foreigners residing in Mexico (of any race) | 1,010,000 | <1.0% | 2015[190] |

| East Asian | 1,000,000 | <1.0% | 2010[191] |

| Middle Eastern | 400,000 | <1.0% | 2010[192] |

| Jewish | 58,876 | <1.0% | 2020[189] |

| Muslim | 7,982 | <1.0% | 2020[189] |

| Unclassified (most likely Mestizos and Whites) | 107,200,000 | 89.14% | - |

| Total | 126,014,024 | 100% | 2020[189] |

Languages in Mexico (by percentage):[193]